An interesting debate has sprung up in NSW politics, following comments by Premier Chris Minns and Water Minister Rose Jackson that implied the state government may be considering ending local government management of water in the regions.

It was an election commitment that received little coverage, as it was always framed as a measure to prevent Sydney Water and Hunter water from being privatised, but the Minns Labor team have repeatedly said they wanted to amend the NSW constitution to include a guaranteed right to the safe, reliable supply of water, provided by the state government. With the election so narrowly focused on the needs and wants of the state’s city dwellers, it appears that only recently the impact of such a constitutional amendment on regional areas, where water is managed by local governments, has been realised.

For residents in places like Ashley, Attunga, Bundarra, Werris Creek, Gravesend, and plenty of other New England towns and villages who have had to cart or boil water in recent times – sometimes for months or even years – the idea of a protected right to safe drinking water might be appealing.

With almost all the water infrastructure in the region reaching end of life recently or soon, councils across the region have been faced with expensive bills to repair, maintain, or replace significant infrastructure. Multiple major new works like the Quipolly Water Project, raising the Malpas Dam wall, the controversial Dungowan Dam, or the proposed water purification initiatives in Tamworth, are being pushed ahead in search of better water security and reliable town supplies.

And the water bills keep going up and up.

So, what was the response from local leaders to the idea of handing water back to the state government? While some are open to looking at a proposal, others have already committed to fighting the move.

What’s started this?

There are two issues going on that collided in the current debate about ending local government management of water.

The first is the ongoing debate hanging over from the election regarding former Premier Perottet’s alleged plans to privatise Sydney Water, and Labor’s commitment to put it in the constitution of the state so they cannot be privatised.

Speaking at an event in Parramatta during the election on March 19, now Premier Chris Minns expanded that protection to a more broad supply of water for all NSW residents.

“Labor also believes that a guaranteed right to a safe, reliable, supply of clean water — provided by the government of this state — should be a constitutionally protected right for the people of NSW.”

Newly elected, Labor got to work on water safety and security issues by grappling with Walgett. Shifted from river to bore water during the drought in 2019, the salt level in Walgett’s town supply is too salty and unsafe to drink. Water Minister Rose Jackson held a high level meeting in Walgett to address the small town’s water supply issues, and repeated the commitment that all people in the state should have access to clean drinking water.

This is not the first time it has been suggested that the state should be managing water, not local government. In 2008, then water minister Nathan Rees ordered an independent inquiry into the issue. The final report of the Independent Inquiry into Secure and Sustainable Urban Water Supply and Sewerage Services for Non-Metropolitan New South Wales (NSW) recommended that the (then) 106 local water utilities be restructured through regional aggregation into 32 regional entities. The proposal was opposed by many local councils and eventually shelved.

What’s been the reaction?

Apparently suddenly realising that this constitutional amendment would enshrine the right to safe, clean drinking water provided by a state government body to all people in New South Wales and not just Sydney and the Hunter Valley, conservative politicians have voiced their opposition to any such move.

Member for Northern Tablelands Adam Marshall said that while the Premier’s sentiment sounded proper and correct, the corollary was that the State Government would, rather than local councils (the current utility operators), be the supplier of safe and reliable drinking water under the proposed constitutional amendment.

“The fear is this proposal would see all water utilities stripped from our local councils and centralised into various State-owned water corporations or government agencies,” Mr Marshall said.

“Any local control and input, local price-setting powers and public accountability would be completely lost.

“This proposal is absolutely reckless and has clearly not been thought through – it must be ruled out immediately by the new Water Minister.”

Marshall also very quickly declared the hand of the local councils in the Northern Tablelands, vowing they would fight it.

“Our region’s councils will not stand idly by and allow their local communities to be duded by having their local water assets taken off them.”

“They will fight with everything they have and I’ll be the first to join them in that battle to once again defeat this water corporatisation agenda.”

The New England Times asked Mr Marshall to confirm he had spoken to local councils before making this claim, and he said he had spoken to a number of them.

“More broadly, the corporatisation of local water utilities has been a topic often discussed as no council/community wants to lose its water utility, for the obvious reasons,” Mr Marshall said.

The response from local governments in the New England has been more mixed. Gunnedah and Gwydir Councils say they strongly oppose the move. Tamworth Regional Council said they haven’t considered the issue recently, but in 2009 the Council’s position was to oppose a state takeover of water and sewer services.

Interim General Manager of Walcha Council, Phillip Hood, said they too would oppose the move.

“As a small Council, for larger capital works we rely on state government grant support to fund, however if water were to be handed over to state government our levels of service would drop.”

“Water and sewer on-call staff also respond to other functional areas of Council at times, operational costs would increase dramatically if water was corporatised for small regional systems,” Mr Hood said.

General Manager of Glen Innes Severn Shire Council, Bernard Smith, said they haven’t heard anything about changing the arrangements for water management, but councils are best placed to keep doing the job.

“Regional Councils are best placed to continue to provide water and sewerage services and importantly, recognition needs to be given to the important contribution the water and sewerage function provides in assisting the overall sustainability of rural councils through providing organisational economies of scale and efficiencies.”

“Separate water entities are appropriate in the metropolitan context but do not provide overall advantages in the rural setting,” he said.

Others weren’t ready to oppose something that they don’t have any detail about. Liverpool Plains Shire Council said that until a proposal is actually on the table, they are not in a position to comment. Mayor Paul Harmon of Inverell Shire Council has said he viewed the statement with scepticism, emphasising the need for strong clarification around what it means.

Mayor of Tenterfield Shire Council Bronwyn Petrie said they too would need more information.

“Personally, I don’t oppose the concept as water used to be a state government responsibility, however, council and residents would need to be reassured that continued maintenance was carried forth so our community wasn’t left with ageing infrastructure and failing water maintenance.”

“We would need to see the details but potentially that could come at a reduced cost to Council and the ratepayers.”

“However, we are open to discuss the issue and potentially there could be savings for Council and ratepayers if that were the case,” she said.

Armidale Regional Council said Mayor Sam Coupland declined to comment as “he is not across the issue and is not aware of the comments”.

What would be the impact?

Leading local government academic Professor Brian Dollery from the University of New England says “it is disappointing the new NSW Government is again proposing compulsorily appropriating water utilities from local councils in regional NSW.”

“In 2008, a previous Labor Government attempted the same thing.”

Professor Dollery was one of the academics who critically reviewed the proposal to abolish local government water management in favour of about 30 regional services at the time of the independent inquiry report. In further papers published in 2012 and 2013, Professor Dollery and colleagues examined the impact of removing water utilities from local governments. Those works argue that any ‘regionalisation’ of water services will have disastrous results on the financial sustainability of local councils in non-metropolitan NSW. Since ‘bigger is not better’ in water services and the costs of ‘regionalisation’ are prohibitively high, Professor Dollery and Andrew Johnson argued that the NSW state government should instead consider other methods of improving the efficiency of water and wastewater services.

“Revenue from water utilities represents a major source of municipal income.”

“Without this source of revenue, many country councils would not be financially viable,” Professor Dollery said.

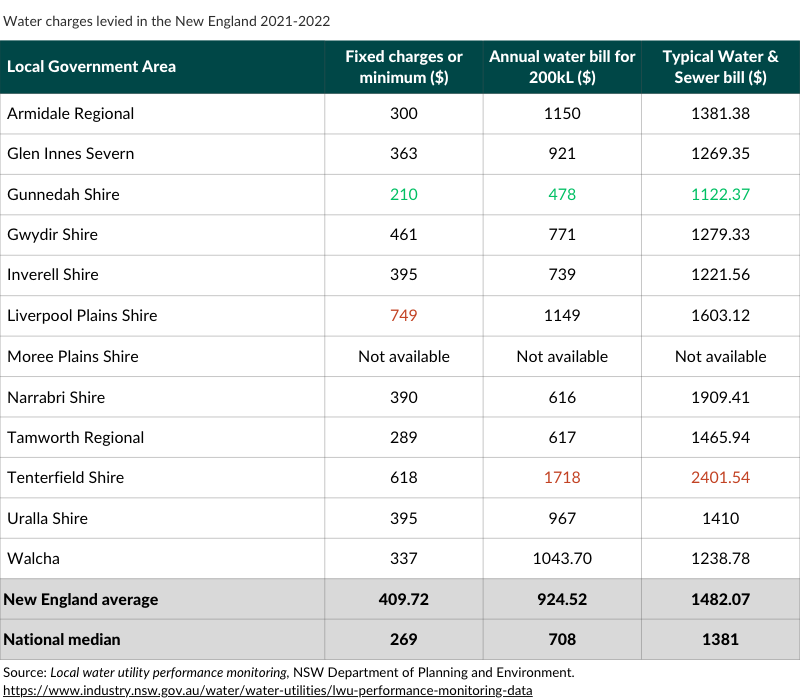

However, with significant variability in water charges across the region, while some councils may be less viable, state managed water may be significantly better for residents. Just within the 12 local government areas of the New England North West, water bills can vary by over $1000 a year according to the NSW Department of Planning and Environment.

Comparing water and sewerage bills is always difficult as each area has their own structure of base rates and scale of usage charges. Plus, water usage is obviously lower in areas with high rainfall than drier places. The following table uses three comparisons: the fixed or minimum charges you need to pay to have the water on at your house, not including any usage; the annual water bill based on a flat 200 kilolitre usage, and the typical combined water and sewerage bill for each LGA. (Note: Moree Plains Shire data was not available from the Department who said the report has not yet been submitted by MPSC. The New England Times has also requested the figures directly from council but as yet we have not received a response.)

On the first measure, fixed charges for water supply only, the highest in the region is the Liverpool Plains Shire Council at $749, $539 more a year than the lowest Gunnedah Shire Council at $210. Gunnedah is also the only council below the national median on fixed charges.

On the second measure, the annual water bill for 200kL usage, reveals that Tenterfield Shire is by far the most expensive water in the state at $1718, hundreds more than the next expensive in the state – Tweed shire at $1370.10 – and the next most expensive in the New England – Armidale at $1150. Gunnedah is again the cheapest in the New England at $478, well below the national median of $708, and with only 5 areas of the state being cheaper.

On the third measure, the typical average water and sewerage combined bill for the LGA, Tenterfield is again the most expensive in the state at a whopping $2401.54 per annum. This is nearly $500 more than the next expensive in the New England, Narrabri, which comes in at $1909.41. Gunnedah is again the cheapest at 1122.37, and the only council to come below the national median on all three comparisons.

One of the potential upsides for some – particularly Tenterfield – and downsides for others – such as Gunnedah – is that it is expected there would be a significant equalisation of this current disparity in water charges if the state was to take over water and sewerage provision.

What happens next

Much of the focus continues to be on sorting the water supply issues in Walgett, and it will likely remain there for some time. Water Minister Rose Jackson made another visit to listen to community concerns on Friday, and the switch to treated river water is on schedule to happen this week, but this is a short-term measure.

Protecting Sydney Water and Hunter Water in the constitution was a key election commitment of the new Labor Government, so they are unlikely to walk away from it, but there has been some softening of language around the constitutional amendment since the election.

Insiders expect that a more detailed proposal for any change to the management of water will surface after the immediate crisis in Walgett is dealt with, at which point we will undoubtedly hear more from local politicians and councils.

Like what you’re reading? Support The New England Times by making a small contribution today and help us keep delivering local news paywall-free. Support now