Forty domestic violence murders have shattered families across the New England region since 1996.

The domestic violence rate in the New England is more than double the state average, and the systemic drivers and obstacles to safety are much harder to contend with.

A four month long New England Times investigation by award winning journalist Lisa Martin has found that while some progress is afoot, fears mount for further tragedies, as many face barriers to accessing safety and support.

Joy rings out over Tamworth’s adventure playground as mums and dads watch youngsters roam the skywalk. Nearby, a large rock in Bicentennial Park tells the tale of a darker side of family life in the New England region.

“Remember those who lost their lives, those who fought to save their lives and honour anyone who is affected by domestic violence,” a plaque inscription reads.

It was the first memorial to domestic violence in the state.

Since 1996, domestic violence-related murders have cut short 40 lives across the New England region. 17 of them in the nine years since the memorial was unveiled in 2016.

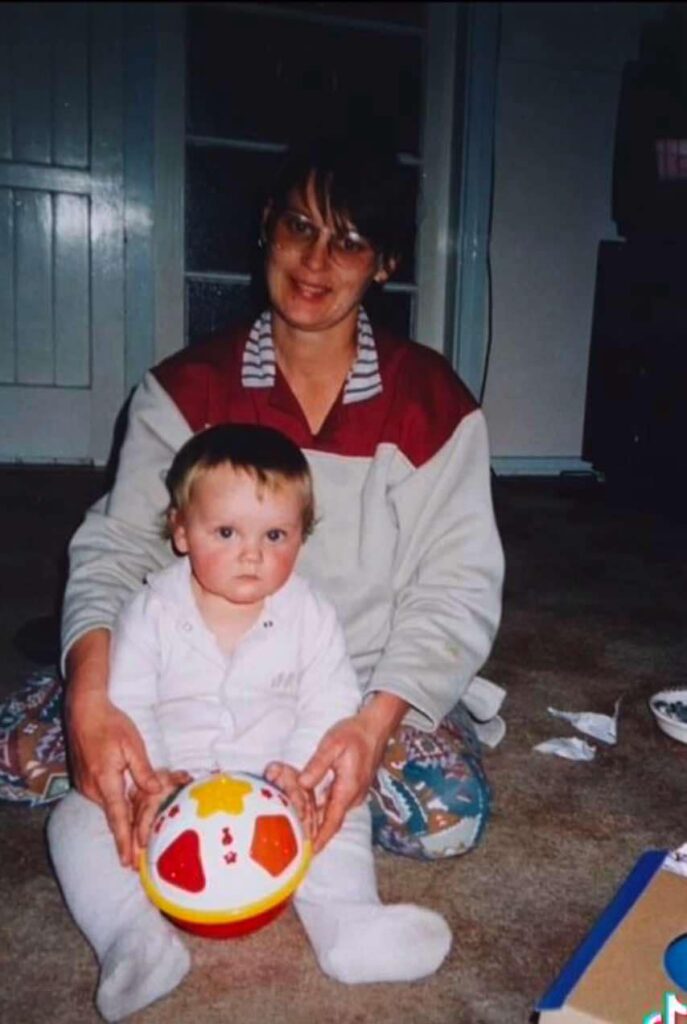

Behind each death, devastated loved ones must plough on with daily life, grappling with waves of grief on birthdays, anniversaries, Christmases, and “random Wednesdays when you’re cleaning your house,” said Inverell resident Jennifer Kemp.

The 24-year-old has life-long physical and mental scars after her mother Michelle, 50, was killed by her husband in a murder-suicide in 2021.

“Every day is a reminder of what was ripped from us,” Ms Kemp told New England Times.

“My mum was a very loving and caring person. She cared for everyone else more than herself. Her children and grandchildren were her whole world.”

On the surface, families can appear normal and happy, because perpetrators modify their controlling behaviour outside the home, experts say.

“In reality, no one knows what happens behind closed doors because the amount of people who said to me: ‘I didn’t know he was like that’ is insane!” Ms Kemp said.

DV a bigger problem and harder to address in the New England

New England is the second most dangerous region for women and children in NSW, according to crime statistics showing a domestic violence rate of 2.2 times the state average.

“You always hear that question: ‘Why don’t they just leave? But we know it’s more complex than that in a rural context,” said Armidale-based researcher Kyle Mulrooney from the Centre for Rural Criminology.

A lack of anonymity and privacy in tight-knit communities can discourage some from seeking help.

“You don’t want to be the town’s focus of gossip,” Dr Mulrooney said.

Victims also hold a strong sense of shame.

“People think it’s their fault. They feel really disempowered and then they don’t speak out and they lose their voice,” University of New England Professor Rikki Jones said.

Country areas “can be a ripe environment for coercive control,” Dr Mulrooney said, noting a lack of public transport can make the logistics of escaping even more difficult.

“If you’re out on the land and your abuser coercively controls you… how do you take a bus if there are no bus routes?” he said.

Financial pressures and low income can also trap victims in violent relationships. About 17 out of 20 people in the region don’t have any money set aside for emergencies and poverty forces many to skip regular meals, Dr Jones noted.

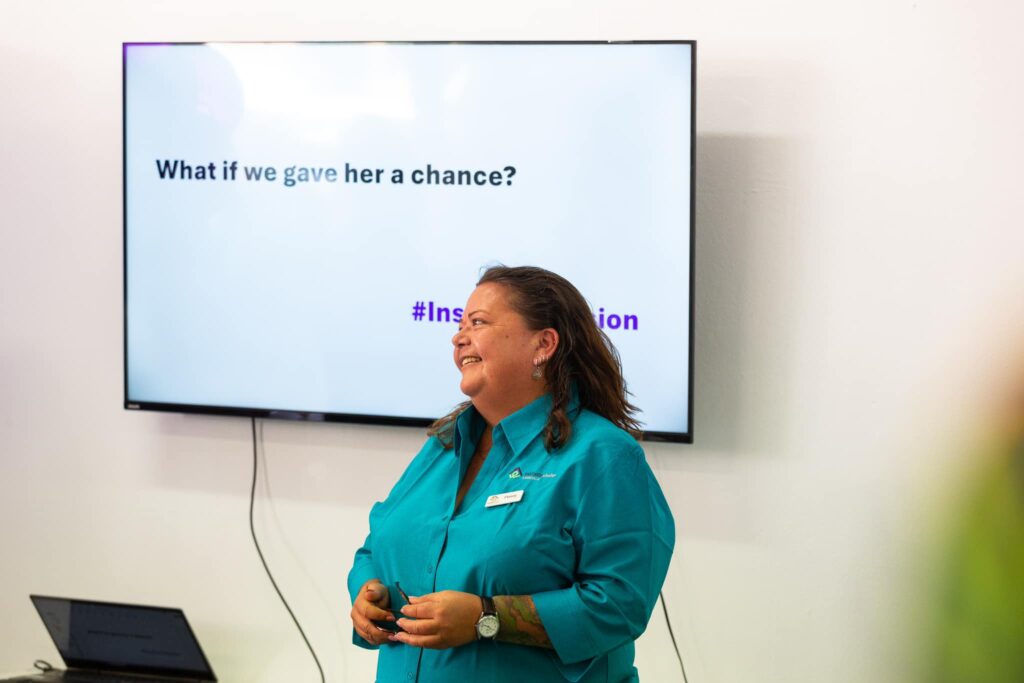

Women’s Shelter Armidale – the second oldest in the state – deals with this reality daily, providing 11,400 frozen meals to families in crisis a year.

“If we don’t start looking at the drivers of violence in the home – not enough food, not enough money to pay rent, a crappy place to live, no social supports, nothing good to live for… then we are never going to stem the tide of violence,” shelter chief executive Penny Lamaro said.

A shortage of rental properties and crisis accommodation is another obstacle victims can face. Frequent natural disasters, such as floods and bushfires, damage homes and further strain housing availability, Dr Jones said.

Women’s Shelter Armidale supports around 350 women and their families a year. The shelter has four bedrooms and four units for crisis accommodation and 12 transitional houses.

“We haven’t had a room empty in years now,” Ms Lamaro said, adding that her organisation fundraises $200,000 a year to cover hotel rooms.

Upon arrival at the shelter, past events and liabilities can haunt women seeking safety including “social housing debts of $20,000-$40,000,” Ms Lamaro said.

“It’s a very common form of abuse – the housing will be in her name and if… he’s controlling the money and doesn’t pay the rent, if there’s damage to the house, it’s all in her name,” Ms Lamaro said, adding that theoretically under the law, family violence victims are not supposed to be saddled with that debt but some social housing providers push back.

However, leaving home is not the only choice. Sora (formerly Tamworth Family Support Services) has a program that helps women stay in their homes while leaving abusive relationships. Under the scheme, there is access to free safety audits of residential properties, partly subsidised safety upgrades and legal support for apprehended domestic violence orders.

Some medical personnel across the region are getting training to recognise domestic violence red flags and connect patients with lifesaving services and mental health support, thanks to the local primary health network.

But in some communities, it can be difficult for victims to access affordable counselling – with some psychologists and counsellors costing up to $250 an hour. In some towns, there are long waiting lists for counselling.

A shortage of GPs in the region also means it can be hard to obtain mental health plans that grant 10 Medicare-partly subsidised psychology sessions. Women’s Shelter Armidale now has an onsite GP to combat this problem, Ms Lamaro said. However, out-of-pocket expenses from the Medicare sessions can put counselling out of reach for many.

Alternatively, NSW Victims Services offers up to 22 hours of free counselling.

Police drained by DV demands

Domestic violence makes up the lion’s share of operational police work across the New England region. Dr Mulrooney characterised rural police resources as stretched, and said there are problems with staff turnover, mental health resignations and recruitment struggles.

The region is carved up into two police districts – Oxley has 172 officers and the New England district has 189. They cover a combined 98,370 square kilometres, an area equivalent to South Korea.

“The contact that survivors have with police is so influential if they have a bad experience the likelihood that they’ll engage police again drops massively,” said former Armidale resident, Bridget Harris, who now works for the Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre.

A shortage of female officers can affect how supported women victims feel during the criminal investigation and legal process, experts said.

The New England and Oxley police districts have a gender breakdown of around 66 per cent male to 34 per cent female officers.

Some male officers feel uncomfortable dealing with domestic violence incidents and prefer to focus on the criminal process, whereas female officers generally have a much more empathetic approach, Dr Jones noted.

A pilot program between Armidale police and Sora, in which a specialist domestic violence social worker is embedded at the station during business hours, is helping to address that issue.

Cultural differences complicate matters

Indigenous people make up more than 10 per cent of the New England population, according to census data, but are overrepresented in domestic violence statistics.

It is not clear to what extent there is a greater rate of domestic violence in these minority groups, or there is a high rate of reporting, or a higher rate of police recording offences because of the other activities NSW Police engage in with local Aboriginal peoples.

In New England, like in other parts of Australia, indigenous children are placed into child protection at a greater rate than non-indigenous youngsters. Fears about child removal mean many indigenous women are reluctant to self-report domestic violence to the police. Neighbours or strangers generally instigate callouts, social workers said.

Additionally, experts and social workers say that there is an ongoing problem is police misidentifying victims as the primary aggressors, and that this is common with indigenous and migrant communities.

NSW police said there was no reliable method to quantify the extent of misidentification in domestic violence cases, however, a working group was examining the issue.

Dr Harris said it was vital police understood colonial history and how it can shape indigenous victims’ behaviour.

“In terms of First Nations survivors if you don’t understand the colonial history then police turning up might feel a survivor is being aggressive when they are showing fear or tension that they have with police based on this history,” Dr Harris said.

Helping to build better trust between indigenous communities and police is the presence of Aboriginal liaison officers at some stations. New England and Oxley police districts have these civilian officers serving in Armidale, Inverell, Moree, Tamworth, Gunnedah and Boggabilla.

Building better trust, and better systems

Aside from strong cultural awareness, police also need training on how trauma can present in family violence victims, so women’s stories are believed, Dr Harris said.

“A lot of the time when (police) arrive on the scene, survivors might be experiencing a neurological trauma if they have experienced a head injury or been strangled,” Dr Harris said.

“They might not have the emotional response that police expect. They might not be crying; they might not be visibly upset. They might be angry. They might seem really calm. Someone might seem like an unreliable witness because they jump around chronologically.”

A NSW Police spokeswoman said officers undergo mandatory training each year on a wide range of domestic violence issues including coercive control, victim support and cultural awareness education.

The NSW justice system is trialling other improvements.

A specialist family violence court pilot at Moree and Gunnedah since September 2023 has aimed to make the legal process smoother and less traumatic for victims. Under the arrangements, a trauma-trained magistrate oversees the entire family violence case. The emotional toll of giving evidence is acknowledged and victims are offered regular breaks. Proceedings are also in plain language, not legal jargon.

Back in Inverell, Ms Kemp hopes her family’s tragedy can be a lesson for others.

“I know it’s easier said than done but leave at the first red flag. Don’t stick around thinking it’ll get better with time. Because it never does. It’ll continue to get worse little by little,” Ms Kemp said.

“There is help out there and it’s always better to be alone than to be abused and have your children grow up thinking it’s normal to be hit, screamed at, controlled and never able to have any free time or freedom.”

This is part of an investigative series about domestic violence in the New England. Join us tomorrow to find out how a targeted program designed for our community was denied funding.

WHERE TO ACCESS SAFETY AND SUPPORT FOR FAMILY VIOLENCE

- Police – 000

- Empower You – NSW Police app for documenting abuse and accessing support

- Women’s Shelter Armidale – 1800 005 352

- Sora (Formerly Tamworth Family Support Services) – 1800 073 388

- Centacare New England – 1800 372 826

- Anglicare – 02 6701 8200

- Gunnedah Family Support – 02 6742 1515

- Allawah Cottage Gunnedah emergency accommodation – 02 6742 4193

- Armajun Aboriginal Health Service – 1800 276 258

- Aboriginal Legal Service NSW – Tamworth, Moree, Armidale 1800 765 767

- Women’s Domestic Violence Court Advocacy Service – 1800 938 227

- NSW Domestic Violence Legal Advice Line – 1800 810 784

- Domestic Violence Line NSW 24/7 statewide crisis counselling and referral service – 1800 65 64 63

- NSW Victim Services counselling and financial support for victims of crime

- 1800RESPECT 24/7 national domestic, family and sexual violence counselling service

- Mensline 24/7 phone and online counselling for men – 1300 78 99 78

- eSafety Commissioner – online safety checklist if you’re experiencing tech-based domestic, family and sexual violence

- Kids Helpline 24/7 phone counselling with young people aged 5-25 – 1800 55 1800