In Part 1 of our investigation into the poverty surge in the New England we learned all signs indicate the New England region is facing an escalating crisis of poverty and economic disadvantage. Inequality in the region is deepening, and the cost of living crisis is forcing many to forgo essentials, with some made homeless.

But why? After a huge surge in interest in regional living, and Armidale or Glen Innes frequently topping the list of desirable locations to move to, it doesn’t make much sense.

Several leading voices have gone on record raising their concerns and observations about why poverty is rising in the region, with housing – or lack of it – topping the list of concerns.

With increasing numbers migrating to our region in search of the good life, great jobs, and our welcoming communities, the availability and cost of housing has spiralled out of control, being the main – but not the only – driver of the surge in poverty.

Housing the key driver of current situation

One of the most pressing issues facing the New England region is the lack of affordable housing. Homes North CEO Maree McKenzie has worked in social housing for over 30 years and says the region’s housing challenges have intensified dramatically over the past 15 years.

“In regional areas, we’ve always had disadvantaged people, but we haven’t seen such inaccessibility to affordable housing as we have now.

“This is something that’s been developing, particularly in towns like Gunnedah and Narrabri,” McKenzie said.

McKenzie pointed to several factors that have worsened housing affordability in the region. These include rising property prices fuelled by investors, changes in negative gearing and capital gains tax, and economic developments like the growth of the mining sector.

“When investors started buying up properties in areas with high demand like Gunnedah and Narrabri, rents skyrocketed. They would lease them to mining companies for a premium, and after a few years, they’d sell for capital gains,” she said.

According to McKenzie, this trend has spread across New England, pushing out local families and making it difficult for low-income earners to compete.

“Twenty-five years ago, local people owned their homes and rented them out at a reasonable rate. Now, investors have taken over much of the rental market, maximising returns and driving up prices.”

The region’s housing issues were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, and repeated natural disasters, which saw an influx of city and coastal dwellers migrating to regional towns.

“It doesn’t take much to move a vacancy rate in a small town from 3.5 to 1.1 percent. That internal migration made it even harder for low-income renters to find housing,” McKenzie said.

Numbers all align

New research commissioned by the Regional Australia Institute shows the number of city-dwellers looking to relocate to the regions has doubled over the past 18 months, demonstrating an urgent need for solutions to regional pressure points.

The results of a nationwide survey released this past week shows 40% of capital city residents are considering a move to regional Australia – up from 20% in May 2023.

Regional Australia Institute CEO Liz Ritchie said the research should ring alarm bells for policymakers, industry and regional leaders.

“Demand for regional living has never been higher, but as a nation we are not keeping pace with delivering the fundamental building blocks that are needed as we rebalance the nation,” Ritchie said.

“Regional Australia is simultaneously experiencing two unprecedented transformations – a once-in-a-lifetime population shift and the net zero transition, which is increasing demand and need for improved services and infrastructure in regional communities,” Ritchie said.

“Falling behind on critical targets is not in the nation’s best interests and we can’t afford to squander this opportunity to better our country.

“Many regions are already struggling with housing, particularly rental markets, and until region-specific policy measures are put in place, this will only be further magnified,” she said.

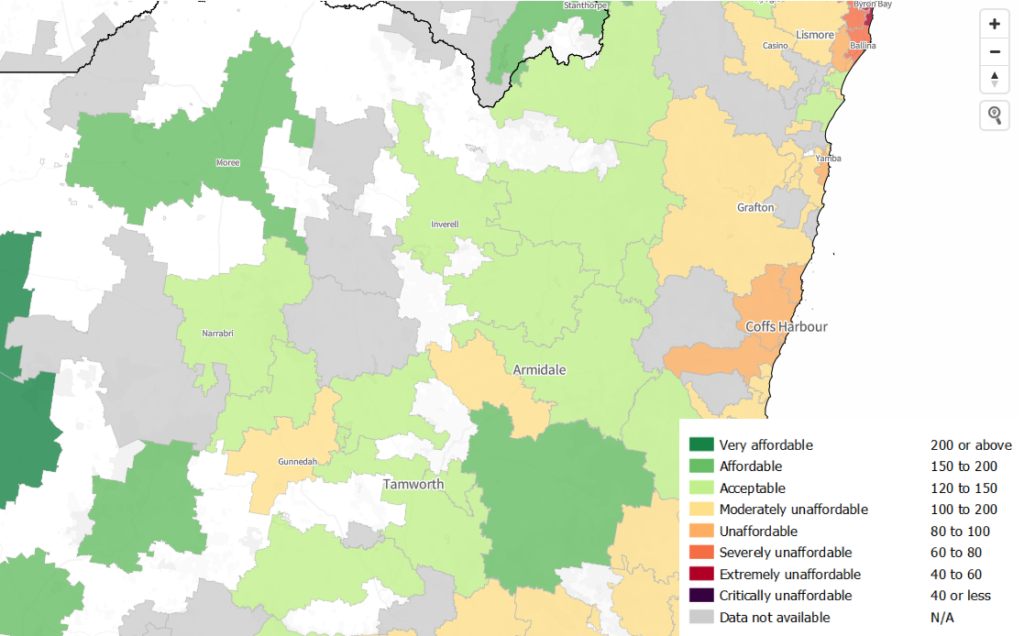

This is confirmed by new data from tenth annual National Shelter-SGS Economics and planning Rental Affordability Index released this week confirms Regional NSW is no longer a reprieve for those looking to escape skyrocketing rents in the city, with affordability in the regions hitting record lows.

The Rental Affordability Index rates the affordability of housing against income levels for that area. Data from the New England shows only Moree and Walcha as having affordable housing, with Uralla and Gunnedah rated as moderately unaffordable.

CEO of Shelter NSW John Engeler agrees with Maree McKenzie’s assessment that what was once affordable is now out of reach.

“The regional rental market is spiraling out of control, with people across the state struggling to afford to keep a roof over their head.

“The regions used to be seen as an affordable alternative for Sydneysiders to escape to when city rents became unaffordable.

“But this is not the case, especially for regional residents on local wages. This is not sustainable and will only get worse as these regional populations grow.”

Fewer jobs, higher costs, complex disadvantage, compound the problem

Major Tony DeTommaso, a Salvation Army Tamworth Corps Officer, believes the surge in poverty is the result of a complex blend of historical and contemporary factors.

“Poverty and disadvantage in New England stem from economic downturns, limited access to education and training, and a lack of affordable housing.

“These are compounded by disparities in healthcare and essential services,” DeTommaso explains.

“Economic fluctuations, shifts in industries like agriculture and manufacturing, and changes in government policies have worsened the situation in recent years.”

For Sandy Avis, a financial counsellor with Centacare for the past decade, the lack of employment opportunities, rising living costs, and shrinking job prospects have created a crisis for many families and individuals struggling to make ends meet.

“It’s getting harder for people for a variety of reasons,” Avis explains.

“There’s a real lack of employment opportunities. A lot of jobs that used to be performed by people, like cashiers, have gone to self-serve machines.

“Seasonal work, such as picking fruit, is in decline, and many factories that once operated in rural areas have relocated to urban centres.”

The disappearance of these jobs has hit the most vulnerable members of the community the hardest. Those on modest incomes, particularly those working in retail and other low-paying sectors, are finding it increasingly difficult to keep up with the rising costs of rent, utilities, and everyday living expenses.

“I spoke to a client who found the cheapest rental she could for $360 a week,” Avis recalls.

“On a modest income, how are you supposed to afford that? Then you’ve got the increase in the cost of living, rising electricity prices – there are all these other demands.”

The situation is even more dire for small businesses in rural areas, which often face higher costs for basic goods.

“Some of these smaller stores are paying two or three times as much for staples that we take for granted,” Avis explains.

This shift has left rural communities like those in the New England grappling with fewer job opportunities, especially for unskilled or entry-level workers.

“Our kids are growing up now, and there aren’t as many employment options. Where can they get a job?” Avis asks.

“A lot of that unskilled labour that kids used to rely on for their first job – working at the local shop or supermarket – has disappeared.”

“A lot of young people are juggling two or three jobs just to get by, but because they’re only casual workers, they can’t get a loan. There are all these blocks in the way that are definitely making poverty and economic disadvantage worse.”

Young, vulnerable people most at risk

Homes North currently manages 2,700 properties across the region, providing both social and affordable housing. In addition to managing properties, the organisation supports people experiencing homelessness, offering them vital assistance.

“We are supporting some of the most disadvantaged people in the region,” McKenzie said.

McKenzie noted that temporary accommodation, while available, is only a short-term solution.

“People are staying longer in temporary housing because there are no permanent options. Moving them into stable housing is taking longer than ever.”

Young people are among the most vulnerable to the housing crisis. McKenzie highlighted that many young people, some as young as 16 or 17, are finding themselves in temporary accommodation, unable to secure rentals due to a lack of references or income.

“They’ve often experienced trauma or domestic violence and can’t return home. Without a rental history or a stable income, it’s impossible for them to afford private rentals,” she said.

McKenzie emphasised that the private rental market has become entirely unaffordable for many young people in the region.

“There’s no private rental that someone on Newstart or income support can afford in the New England North-West,” she stressed.

With limited affordable housing options and an overstretched rental market, the region’s housing crisis is hitting its most vulnerable residents the hardest.

“The housing crisis is affecting everyone, but it’s particularly harsh on young people and low-income families.”

Sick are more at risk due to lack of healthcare

One individual from Northern NSW, who we’ll call Jordan, was lucky enough to secure a rental with the aid of disability support on top of their job, but only after a marathon struggle for their own life.

“I went to a rehab facility, and they had to drive me across the road to the hospital on the first night.”

“That’s when I first got diagnosed with type one diabetes. So I don’t know how long I’d had type one diabetes, because it never got diagnosed, never checked my blood glucose, and when they did check it, it blew the machine off the scale it was so high. The equipment couldn’t even read it.”

“So I was in all sorts, in a lucky, very, very lucky, to survive. And since then, I went on to complete the program successfully.

“I manage my type one diabetes and liver cirrhosis. I have to inject insulin every day. But, I mean, the whole thing about this is that that’s what happens over long periods of time of substance use and like it will damage all aspects of your life.”

Another individual, we’ll name George, knows all too well what it’s like to go without – they’ve been roughing it on the streets for over twenty years.

“I’m very used to it, and it’s not the way of life anyone would ever want to live, but I’ve been living it.”

George is on a waitlist to be hospitalised for a decades long illness.

“It could be next week, It could be in ten weeks. It’s just no good.”

“You kind of have to sleep with one eye shut and one eye open when you’re out here.”

“I just want to have a normal life, you know? Find a place and settle down. It’s just no good.”

Jordan now works for an arm of Vinnies which, in a poetic twist, involves helping people who find themselves in a similar spot they were in. It’s been a huge turnaround of fortunes for Jordan since working with an organisation that is having a crack at solving a seemingly impossible task.

Affecting more than you can see

While Jordan is one who didn’t fall through the cracks completely, there are many who are still fully stretched even holding down a 38 hour job without the struggle of addictions. Clare Van Doorn, the regional director of Vinnies, has seen first-hand the growing number of people seeking assistance, not just the unemployed or part-time workers but also the “working poor” – individuals employed full-time but still unable to meet basic living costs.

“It’s evident in the different demographics of people seeking support. We have people who are working full-time, but they’re really struggling with the cost of living crisis and the housing crisis. It’s impacting everywhere,” said Van Doorn.

Van Doorn stressed that there simply isn’t enough social or affordable housing available to meet the growing demand.

“We just don’t have the current assets or units in the region or remote areas. There’s nowhere for people to have secure housing or tenancy.”

This housing dilemma has worsened due to increased migration from urban areas to regional ones as people seek more affordable living conditions. However, as Van Doorn points out, the reality is that New England’s housing market is ill-equipped to handle the influx.

“People are moving out of urban spaces and into regional areas seeking affordable housing, but there is just not enough housing available for them,” she explained.

The broader cost of living has also become a significant issue in the region. Van Doorn noted that basic grocery costs are higher in regional areas, even though wages remain stagnant.

“The cost of basic staples is higher, but wages are no higher, so people are feeling the pinch much more in regional communities like New England.”

Adding to the financial pressure is the fact that many fixed-rate home loans have expired in the past few months, which is leading to a further spike in utility and mortgage costs.

“People are already tightening their belts, but there’s a real sense of fear about what’s coming. They don’t know how they’re going to pay when all these new expenses hit at once,” Van Doorn said.

Stress and anxiety takes its toll

This combination of housing shortages, rising costs, and economic uncertainty leads to an undeniable sense of anxiety in the community. Van Doorn described the mood as one of heightened tension, with people becoming more anxious and unsure about their future.

“The level of anxiety is palpable; people are very anxious, and their interactions with others in the community are more heightened than normal,” she noted.

Natural disasters and rising living costs have also added to the region’s challenges, creating a perfect storm for families who are already vulnerable. And, as we learned in an earlier investigation, many refugees from the flood ravaged Lismore region have relocated to the New England, finding higher ground, but still vulnerable to homelessness and poverty having lost so much already.

Van Doorn pointed out that people are not only dealing with the cost of living but are also trying to recover from the effects of these disasters.

“There are so many layers of stress. People are thinking, ‘How am I going to survive?’”

Particularly concerning is the disproportionate impact the crisis is having on First Nations communities in the New England. While they make up a smaller percentage of the overall population, Van Doorn stated that around 49% of the people Vinnies supports are from Indigenous communities.

“It doesn’t affect everyone equally, and First Nations communities are bearing the brunt of the housing crisis.”

In Van Doorn’s view, the housing shortage remains the most significant issue.

“Regardless of everything else, I think the housing side of it is the biggest factor at the moment.”

In our final part of this investigation, we’ll look at a few ideas of what can be done.

Our thanks to Steve Katte, Jo Dolan, and the Investigations Team for contributing to this investigation.

If you need help or are upset by this story, please seek support.

- 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732)

- Lifeline 13 11 14

- 13Yarn 13 92 76

Like what you’re reading? Support The New England Times by making a small contribution today and help us keep delivering local news paywall-free. Support now