Something went very wrong in Toomelah in the local government election in September.

While the 93% informal rate in Toomelah is clear evidence that something wasn’t right, the more we looked, the issues were not limited to Toomelah.

Every single booth in the Moree Plains Shire Council election, as well as postal votes, had issues in the count.

In the next part of our investigation, we delve deep into the voter data file to find out how widespread the issues are, and whether it might have made a difference to the result.

A bigger problem than undervotes

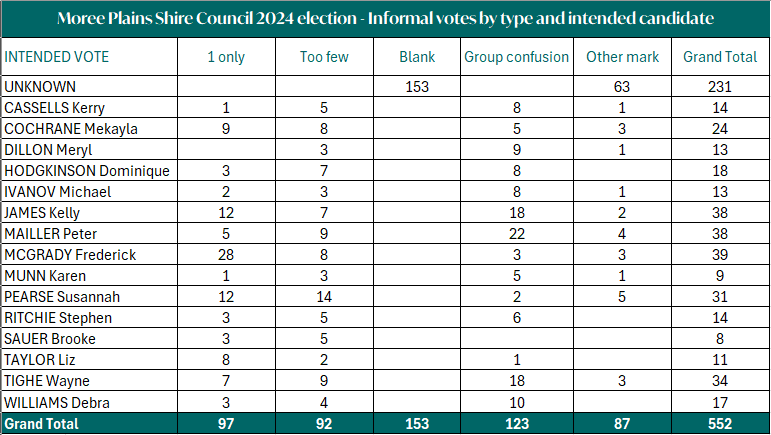

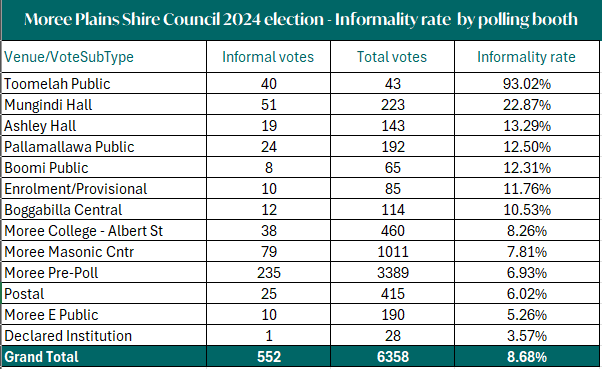

There were 552 informal votes recorded in the count of the Moree Plains Shire Council election, an informal rate of 8.68%.

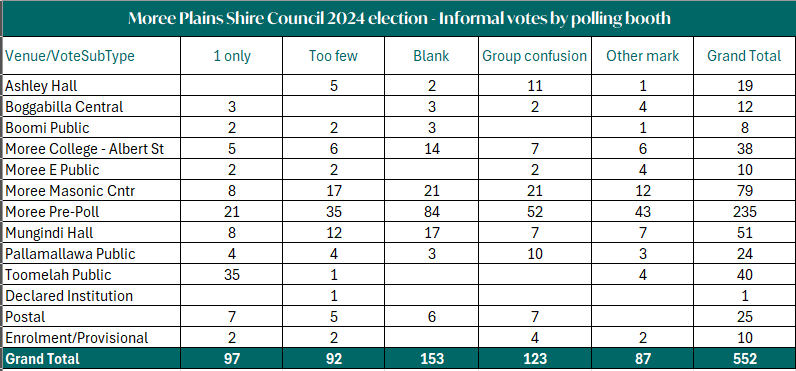

In Toomelah, where our investigation began, the vast majority of informal votes were what is called ‘undervotes’ – voting for less than the minimum required. 189 undervotes where the voter’s intention was clear were not counted – 97 put a ‘1’ only, while 92 voted for between two and four candidates.

153 ballots were left blank, which are obvious informal votes and happen in every election.

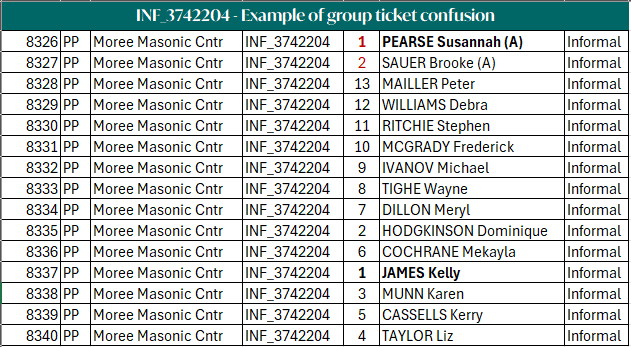

A significant proportion of the informal votes were voters getting confused by the ballot paper design and instructions, and voting for candidates in the group, and candidates in the ungrouped column, as though there were two separate races. As these votes contained two ‘1’s – one for a group candidate and one for an ungrouped candidate – it is not possible for any savings provisions to retain these votes.

This group confusion may be particularly disheartening for some voters to learn, as most of the 123 votes discarded show they went to some lengths to vote correctly, voting for more than the minimum five candidates.

87 voters made some other kind of mark – either whatever they wrote on the ballot paper was not a number, had no ‘1’, or more than one ‘1’. A notable number have marked 5 or more candidates – but with the same number, rather than sequential numbers – indicating another interpretation of the less than clear instructions.

Of these, 24 could still be clearly identified as voting for a particular candidate, such as when they only make one mark on the ballot paper next to one candidate, it’s just not a number. Physical inspection of the ballot paper would be required to determine what the voter was trying to do and if it is possible to count the vote for the remaining 63.

All told, 189 ‘undervotes’ where the voters intention was clear, plus 24 other votes where the intention of the voter was clear, gives a minimum of 213 votes, or 38.6% of the informal votes (3.4% of the total vote) for Moree Plains Shire, could have been counted on election night.

123 votes where poor ballot design or lack of effective instruction caused confusion, plus up to an additional 63 where the voters intent may be clear on physical inspection or some other error may have occurred, gives a further 186 votes lost in the Moree Plains Shire to a failure of the NSW electoral system.

These electoral irregularities affected every candidate, and every voting booth in the Moree Plains Shire.

The NSW Electoral Commission said “in the coming months the counting and results team will undertake an analysis of ballot paper markings to determine any trends with informality. This information will be incorporated into our post election report.”

Everywhere, not just Toomelah

The stark result in Toomelah gave the impression it was an isolated issue that was likely to be something as simple as a booth worker giving poor instructions. However, when it became apparent from reports from locals that they weren’t given verbal instructions, questions were then raised about literacy levels.

These questions intensified when it became clear that all of the outer villages, which have substantially lower rates of education, and much higher rates of disadvantage, all had double digit informality rates. Only the Moree booths, which make up most of the voters, had informality rates in the usual range.

Dr Sally Dixon, who heads the linguistics program at the University of New England, says it’s not possible to assess whether the instructions written on the ballot paper would have been clear to an average voter.

“It’s not really possible to say for certain whether ‘the average person’ would interpret the instructions in a particular way, because it’s not possible to say what English proficiencies ‘the average person’ has,” she said.

“The population of NSW has a great deal of diversity in proficiency with Standard Australian English, written and spoken… the question for institutional English in the NSW context is therefore whether it works with a variety of proficiencies.

“Both linguistic and cultural differences can impact on the success of a piece of communication.”

Dr Dixon said the Toomelah community itself had previously identified adult literacy as a significant problem, reaching out to the University of New England and Aboriginal literacy charity Literacy for Life for assistance.

“That might indicate that residents of Toomelah have different proficiencies with written Standard Australian English than assumed by the people writing the instructions, and following that, it might be that this impacted on how the instructions were followed.

“This is a certainly one possibility that the NSW Electoral Commission should explore with Toomelah residents as a matter of urgency to ensure that they are not disenfranchised by NSW electoral processes.”

Clear differences in the type of informality, with Ashley and Pallamallawa having a much higher concentration of group ballot confusion, in comparison to the undervoting issue in Toomelah, Boomi, and Mungindi, indicates that community and communication differences could be readily identified and addressed if there was the will to do so.

Questions have been put to the NSW Electoral Commission around how they determined the design of the ballot paper and whether they specifically considered disadvantaged groups in that process.

Design failure the responsibility of the Electoral Commission

The NSW Electoral Commission has confirmed that the instructions on the ballot paper are not able to be altered, that if asked for assistance, polling booth workers may only read those instructions, and no instructions regarding groups are given on the ballot paper on how to treat groups. It is by design that voters are left to figure out for themselves what they are supposed to do.

“The voting instructions on ballot papers are set out in legislation, which must be followed by the NSW Electoral Commission,” the spokesperson said.

“Only when there are groups with group voting squares ‘above the line’ will there be specific instructions about group voting.”

Moree Plains Shire Mayor Susannah Pearse said if she had known that hers would be the only group on the ticket then she may not have done it.

“Of course you want the best position on the ballot paper which is why we did it.”

“We didn’t know we’d be the only group though.”

The NSW Electoral Commission said they do not reveal until after the close of nominations if there are any groups on the ticket, nor do they give any advice to candidates on whether to have a group on the ballot or not. They did not offer, and would not have allowed, Pearse and her running mate Cr Brooke Sauer the option to drop the group to make it easier for voters.

“I had lots of people telling me that they way we appeared on the ballot was confusing – but I don’t get to decide how the form of the ballot paper,” Mayor Pearse said.

“Absolutely I did not want voters to be confused.”

A spokesperson for the Minister for Local Government, and the Office of Local Government directly, reiterated multiple times that while they have carriage of the Act and Regulations, they do not prepare nor decide the regulations relating to the management of local government elections, the NSW Electoral Commission does.

In the last local government election in 2021, there were four groups on the ballot in Moree Plains Shire. While the informal rate was considerably lower at 4.75%, the same pattern of people voting for the grouped candidates and ungrouped separately, or treating each column as a separate race, is clearly evident in dozens of votes.

Count issues linked to over-confidence in the computer system

The NSW Electoral Commission is yet to answer questions about how the form of the ballot paper came to be, but they have answered questions about the count.

“After the initial count of the first preferences on the election night, all the ballot papers underwent a second count, that is referred to as the check count,” the spokesperson for the NSW Electoral Commission said.

“This includes all preferences marked by an elector on each ballot paper being manually entered into the computer count system by a data entry process. This includes every preference on every ballot paper, i.e. including ballot papers where the markings are obviously informal, or that the officials were uncertain how to sort during then initial count.

“This process is completed separately by two election officials. The first official enters all preferences marked on the ballot paper into the count system. The second official also enters all preferences marked on the ballot paper into the count system, without seeing what the first official entered.

“The count system then completes a check whether there is any difference in the data entered by the two officials. Any difference must be reconciled before the preferences on the ballot paper can be confirmed as correct.

“After the data is entered and checked, it is the computer count system that confirms ballot paper formality and completed the distribution of preferences to determine the elected candidates.

There’s a number of failures in this process, almost all of which are the reliance on a computer to do judgements that require a human eye – and in the act is indicated as ‘in the opinion of the returning officer’ – and a belief that double data entry will fix any errors.

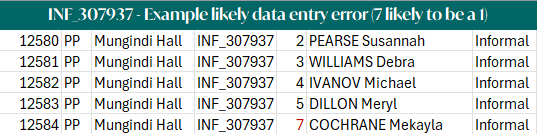

Wherever and whatever the limitations of this process, multiple data entry errors were identified in the Moree Plains Shire vote data file. Clearly incorrect numbers, apparent confusion of 7’s and 1’s, 8’s and 3’s, and other odd entries.

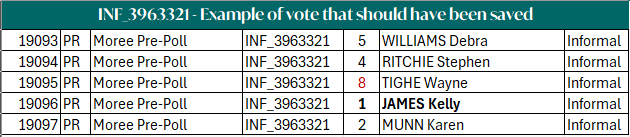

Then, when the computer – not a human – determines votes are informal, the system seems to be unable to apply two savings provisions simultaneously, or deal with anything more that a single problem. So in the event that data entry error creates two breaks in the sequence of votes – such as this vote, where the 3 has been entered as an 8, meaning the 3, 6, and 7 are missing from the sequence, the vote has not been saved despite there being more than 5 candidates voted for, the intent of the voter being clear, and a clear provision for saving votes where there is a break in the sequence (Regulation 345 (2)(b)(ii)).

The NSW Electoral commission has been asked to explain what our investigation uncovered, and what processes they have for a human to check the ballot to straighten out such anomalies.

Similar data entry errors were also evident in the 2021 vote data file from Moree Plains Shire. The PRCC computer counting system has been used in every state and local government election in NSW since 2011.

Does it make a difference?

Analysis by New England Times found that the exclusion of those undervotes and other votes where the intent of the voter was clear may change the progress of the count, and potentially the result.

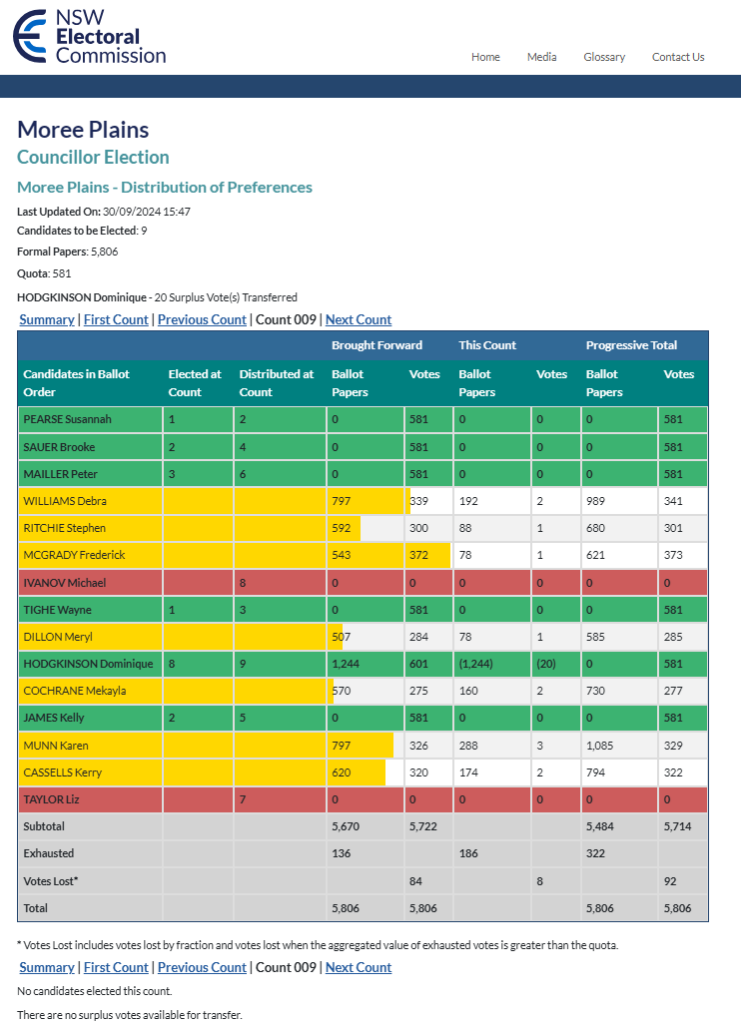

After Count 9, Mekayla Cochrane was on 277 votes, Merryl Dillon was 8 votes ahead on 285, and Steve Ritchie was the next closest candidate on 301 votes. Cochrane was excluded for Count 10.

Adding only those votes where the intent of the voter was clear to the count, without recalculation of the complex additional preference vote transfers and change in quota, Mekayla Cochrane would have been on 296 votes, Merryl Dillon on 289, and Steve Ritchie on 309 votes.

On the surface, it is likely Merryl Dillon should have been excluded at count 10, not Mekayla Cochrane.

We cannot say for certain that would have resulted in Cochrane getting elected, because there are so many variables and complex calculations, and every candidate lost votes to the anomalies uncovered. New England Times has consulted with election academics at the University of Sydney who are currently assessing the data file to determine if they are able to make all the necessary adjustments and create a program to re-count the election.

The only people who can know for sure what the result would have been if the data entry errors hadn’t happened, and savings provisions had been applied, and the undervotes had been counted, is the NSW Electoral Commission. In particular, they are the only entity that can look at the physical ballot papers to determine if the intent of the voter was clear, and if the apparent data entry errors are indeed errors.

If the young, intelligent, and inspiring Cochrane has been deprived her seat on Council due to these system issues, there is likely to be widespread anger as she had developed many admirers during her previous term. Cochrane declined an interview, saying she did not want to be seen a sore loser, and by all accounts she’s not – continuing her advocacy for the community in other ways.

However, the Moree Plains Shire Council has indicated they have little appetite for revisiting the election, despite being very aware of the issues in the count. A spokesperson for Council confirmed that they recommended the more expensive by-election over a countback for vacancies because of the informality and the closeness of the race, particularly at count 9 and 10, but they’re getting on with business.

“Council staff carefully considered the options available to it in relation to Countback and by-election options. The General Manager recommended against the countback option given the high informal vote at [the Toomelah and Mungindi] booths, the close result between candidates (seven votes between candidate nine and ten) and the number of preference counts required (13).”

“Ultimately the decision is the Councillors; and after careful consideration the majority of Councillors opted for the by-election approach.”

“Following each election Council staff always review the process of the election. Council’s General Manager has already flagged with the new Council that he proposes to run a workshop with them to collectively gather feedback on the election process and provide this feedback formally to the Electoral Commission and the Minister for Local Government.”

“The Electoral Commission has declared the results, and the Councillors are now sworn in. Council has moved forward and is getting on with the important business of running the Shire.”

In the next part of our investigation, we look at whether the issues found in the Moree Plains Shire affected the elections of the other New England councils.

New England Times has put a number of detailed questions, including specific examples of what appears to be data entry errors and examples that may have been retained by savings provisions, to the NSW Electoral Commission last Monday, but they were unable to respond in time for inclusion in this story.

A series of questions have also been put to Special Minister of State John Graham, who has oversight of the NSW Electoral Commission, on October 15 but his office has not responded. Those questions were also sent to the Premier’s media team after Graham’s staff did not respond by the initial deadline given.

Read the other parts of this investigation

Like what you’re reading? Support The New England Times by making a small contribution today and help us keep delivering local news paywall-free. Support now