Something went very wrong in Toomelah on September 14, 2024.

43 citizens cast their ballot for the local council election at the Toomelah Public polling booth.

40 of them had their ballots declared informal.

Only 3 had their votes counted.

The NSW Electoral Commission is adamant that was correct.

Almost anyone else says that even if it was right, it was very wrong.

Like the proverbial canary in a coal mine, the electoral irregularity at Toomelah may have revealed a much bigger problem with how local government elections are conducted and counted state wide.

What happened in Toomelah?

When the local government elections were held on September 14, 2024, 43 people in Toomelah went to the local public school to vote, but only three of those votes were included in the vote tally.

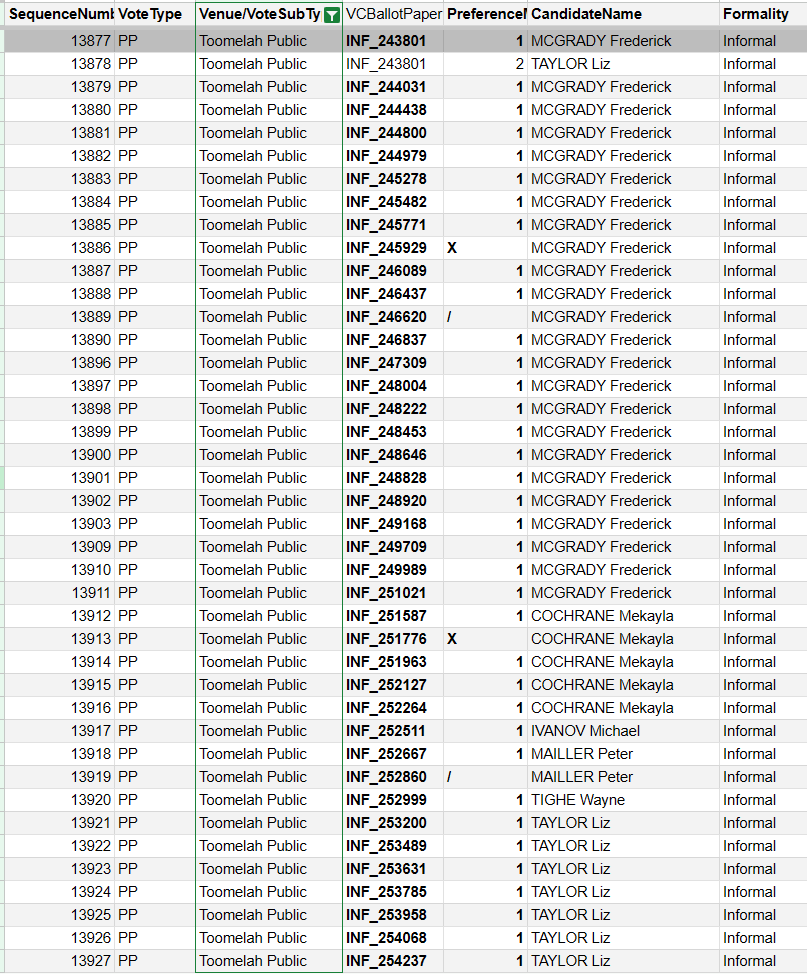

40 people tried to vote, most of them clearly trying to vote for Toomelah’s own Fred McGrady or another Indigenous candidate. But 35 voted just by putting the number 1 in one box, and no other boxes were marked. Four put a mark other than a number against one candidate only, and one voter numbered two candidates 1 and 2.

Because those 40 people did not mark a minimum of five boxes, as the NSW Electoral Commission asserts is required, their votes were not counted.

The why is unclear. This kind of wholesale vote failure at one location would usually indicate that someone was telling voters they could just vote 1. The NSW Electoral Commission denies it was one of their people.

“All three staff working in the Toomelah Public School as election officials have been contacted and stated that the electors did not seek further clarification when issued the ballot paper and directed to follow the directions on the ballot paper,” a spokesperson for the NSW Electoral Commission said.

“The election officials were aware that the only instruction for voting they would give is what is written on the ballot paper.”

Nor anyone else that they know of.

“We are not aware of community members communicating incorrect voting instructions,” they said.

But it’s Toomelah…

Toomelah is a small Indigenous community on the Queensland border, east of Boggabilla, right at the point where the Moree Plains, Gwydir, and Inverell Shires meet, at a pretty spot on the Macintyre River. The population fluctuates, but at the last census was 187.

The tiny community has a long and sad history of abject poverty and deep social issues, right back to when Toomelah Aboriginal Station was originally established as the Euraba Aboriginal Reserve, just south of Boomi, in 1897. It was moved to its current location in the 1930’s.

But they’re not ignorant. Despite apocryphal assertions about informal voting happening in Indigenous communities because of lower education rates or other excuse, the tiny community of Toomelah has a near perfect voting record.

TOOMELAH INFORMAL VOTING RATE 2010-2024

Election Number of informal votes cast Informal vote rate (%) 2024 Local Government 40 93% 2023 State Government 0 0% 2019 State Government 0 0% 2019 Federal Government (remote mobile booth) 0 0% 2016 Local Government 0 0% 2015 State Government 1 3% 2013 Federal Government 2 4% 2012 Local Government 1 5% 2010 Federal Government 0 0%

The newly elected Moree Plains Shire Councillor Fred McGrady is part of why that voting record is impressive. While the 72 year old Gomeroi Elder hasn’t lived at Toomelah since he moved to Moree to work as a porter on the railway when he was 15, he has served as the community’s returning officer for various elections over the past 20 years and is still deeply connected to the community.

It’s a role he’s always taken seriously, including the responsibility to assist voters to vote formally.

“You give them those instructions, even the most professional voter, you still give them the instructions on what they need to do to make their vote formal,” he said.

Why would I vote for someone I didn’t know?

McGrady is believed to be the first person from Toomelah elected to government. In his own words, Toomelah people often feel disconnected from Council, so to have someone raised and educated in the Toomelah Aboriginal Mission elected to Council is a significant and important turning point.

And it underscores the tragedy of the Toomelah people not having their votes counted.

Cr McGrady worries that his campaign posters may have been partly to blame in what happened at Toomelah. The very typical ‘Vote 1’ campaigning, with no preferences indicated, has been a standard form of electoral matter in the New England for some years, so it is unlikely his posters were the problem. His social media posts with the poster included the line “To make your vote truly count, make sure you mark 5 squares on your ballot.”

But it is a measure of the man that he, unlike the NSW Electoral Commission, is prepared to accept some responsibility.

“I think a lot of people just read vote 1 Fred McGrady,” he said.

A week after the election, and before the count had been declared, McGrady’s brother and his partner who live in Toomelah came to Moree for a funeral, and he asked them what happened.

“They said ‘well, we weren’t given instructions. They just handed us the ballot paper and we went and voted.’”

“If you’re not given those instructions, why would we vote for somebody we didn’t know?”

McGrady says he raised the issue with authorities before the race had been declared. He didn’t wait to find out if he had been elected. He, and others, were largely ignored.

He feels sorry for fellow Gomeroi candidates Mekayla Cochrane and Liz Taylor, who also lost a number of votes to formality issues, but were not elected. And he is scathing of the NSW Electoral Commission, saying the vote count is a reflection on them, not the people of Toomelah.

“The NSW Electoral Commission’s incompetence failed the Toomelah constituents, denying their right to exercise their constitutional rights, to cast a formal vote for their preferred candidates.”

“This is a wake-up to ensure that Aboriginal people are involved in the process, and that they are given the instructions on how to legally participate in our democracy.”

Why didn’t the savings provisions didn’t kick in?

Electoral systems around the world have rules called ‘savings provisions’ that provide for votes to be counted even if they are technically informal, as long as the intention of the voter is clear.

In the most simple terms, if there’s a clear vote 1 for someone, you count it anyway, even if they stuffed the rest of it up.

The premise is that if a voter has gone to the trouble of attempting to vote correctly, the system should do everything it can to find a way for their vote to be counted.

Those votes where you can’t figure it out – like when there’s two 1’s on the ballot paper – or it’s clear that they intended to not vote for anyone – like leaving the ballot paper completely blank – will always be informal. And there will always be informal votes. But the vast majority of informal votes are mistakes, and the system is supposed to have your back: if the voter’s intention is clear, count the vote.

The savings provisions for local government elections in New South Wales are identical to the NSW state government election provisions, and very similar to the federal rules, each with the general underlying principle that if the intent of the voter is clear in the opinion of the returning officer, then you count the vote.

This did not happen in Toomelah.

This did not happen anywhere in the State, for any voter that numbered less than the minimum required of preferences indicated on the ballot paper.

According to the NSW Electoral Commission, this is correct. The savings provisions do not provide for votes with less than the minimum required number of preferences on the ballot.

Professor Graeme Orr from the University of Queensland, a leading expert on electoral law, said the explanation from the NSW Electoral Commission is right.

“The law does not ‘save’ these ‘undervotes’. It only saves certain errors, such as repeating a number, or using a tick instead of a ‘1’.”

“Its aim is to avoid ‘plumping’, where people just vote ‘1’. Because if most people do that, you don’t have a system based on proportionality or preferences, but a ‘first past the post’ system.

“The current law is designed only to ‘save’ people who make obvious unintentional errors of numbering, but are otherwise trying to follow the requirement to choose at least 5 options.“

This design has resulted in the situation where a voter who numbered their ballot 1,2,3,4 – with their vote for four candidates very clear – have their ballot declared informal and discarded, but someone voting 1,2,2,3,4 – with their preference unclear, except for the first candidate – had their vote saved and counted.

It has also resulted in 189 citizens of the Moree Plains who voted with less than five preferences being disenfranchised; at least 36 of them in Toomelah.

‘Inelegant’ law buried in regulation

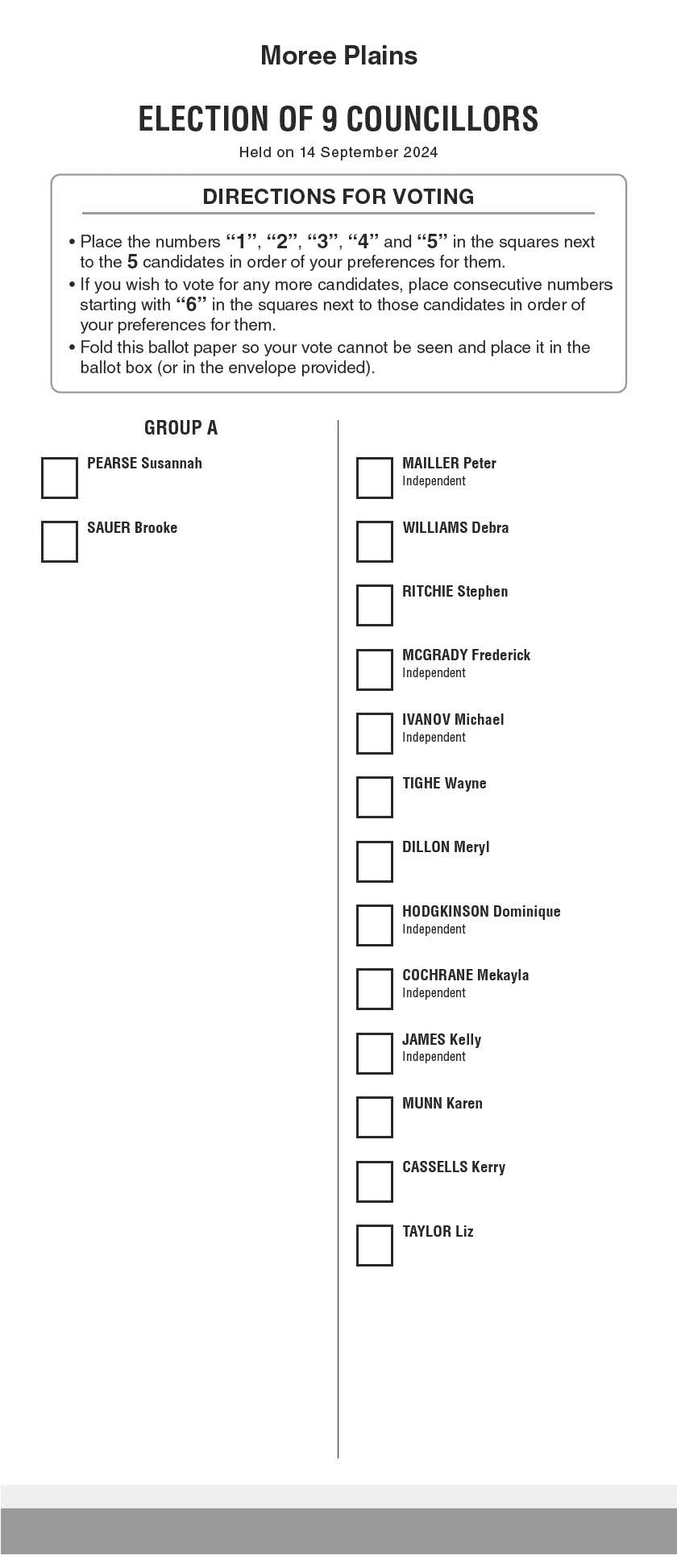

There is no requirement in the Local Government Act 1993 for a minimum number of preferences to be on the ballot.

There is no requirement for a minimum number of preferences in the relevant section 345 of the Local Government (General) Regulation 2021 either.

The only place any mention of a number of preferences appears is on the form for the ballot paper.

“Section 345 of the Local Government (General) Regulation 2021 provides that a ballot-paper is informal if the elector has failed to record a vote in the manner directed on it,” said the spokesperson for the NSW Electoral Commission.

“Section 305 of that regulation requires the ballot paper to be in the form of Form 5 in Schedule 11 to the regulation.”

“Form 5 provides the directions for how a vote is to be recorded on the ballot paper.”

Form 5 has this instruction of what should appear on the ballot paper:

“Place the numbers [here insert the sequence of numbers that corresponds to half the number of candidates to be elected] in the squares next to the [here insert half the number of candidates to be elected] candidates in order of your preferences for them.

If you wish to vote for any more candidates, place consecutive numbers starting with [here insert the next number after half the number of the candidates to be elected] in the squares next to those candidates in order of your preferences for them. [Where half the number to be elected is a fraction it is to be rounded up to the next integer]”

The form does not include any language or instruction that you must number a certain number of boxes to make your vote count, as the federal ballot papers do.

Orr believes the law could be reformed to save as many votes as possible – and relatively easily, as the restriction is only in regulation, not the legislation.

“It’s an inelegant way to lay down the rules for an important practical and political matter.”

“But since it’s buried in the Regulations, not the Act, it is something that the [Local Government] Minister could amend or improve on without full parliamentary debate.”

A spokesperson for the NSW Minister for Local Government, Ron Hoenig, says the Minister has no role in the administration of elections, and referred all questions back to the NSW Electoral Commission.

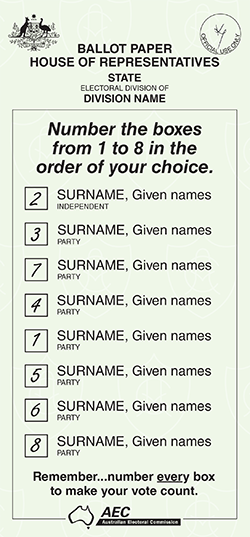

However, Orr believes there is a more substantial issue with the way elections are conducted in NSW, which is that we have too many different systems.

NSW citizens face an array of different requirements when they head to the polls:

- Federal House of Representatives, which has compulsory preferences

- Federal Senate, which has partially optional preferences, via party box or for candidates below the line

- NSW Legislative Assembly, which has completely optional preferences

- NSW Legislative Council, which is like the Senate but different, and

- Local Government, which is partially optional, can have wards or not, directly elected Mayors or not, and has a variety of different forms of local government ballot paper with combinations of ungrouped and grouped candidates, with and without group voting squares.

“Either we need fewer voting systems, or more generous saving provisions for the more complex systems, such as apply in the Senate,” Professor Orr said.

Recount not a resolution

The irregularity in the voting return at Toomelah was raised with the NSW Electoral Commission long before they declared the race. They chose not to do a recount.

“A recount is only conducted if a request made by a candidate is accepted by the Electoral Commissioner, or on the Commissioner’s own motion. No candidate requested a recount,” they said.

The Electoral Commissioner did not use his own powers to request a recount either.

If they had done a recount, it would not have changed anything, according to the spokesperson for the NSW Electoral Commission.

“The count includes several processes to ensure the accuracy of the data recorded about the markings on each ballot paper.”

“After the data is entered and checked, it is the computer count system that confirms ballot paper formality and completes the distribution of preferences to determine the elected candidates.”

“For this reason, a recount would not have altered the formality decisions about those ballot papers or the results of the election.”

In the next part of our investigation, we will look at how accurate that data entry is, the role of the computer counting system, and if any of the irregularities would have made a difference to the result of the election in Moree Plains Shire.

Top image: The Toomelah town sign (AUJS)

Note: This story has been updated to add the remote mobile polling booth at Toomelah in the 2019 federal election that has been inadvertently left off the table of past informal voting rates.

Don’t miss any of the important stories from around the region. Subscribe to our email list.