The most common request we have had so far is an explainer on preferential voting. There is a great deal of confusion around preferential voting, and is it often a cause of great stress for voters, because there is so much misinformation and disinformation about how to vote in a way that you can be sure your vote will be counted.

Every election in Australia is a little bit different too – how you vote in a local government election is different to a state election, and different again to a federal election. This adds to the confusion.

What is preferential voting?

Preferential voting is the name for our voting system where you rank the candidates in your order of preference. (It’s also called Alternative Voting because you indicate who your alternative is.)

Preferential voting is also sometimes called “instant run off” voting. This is because the end result is the same if you had a run off election – which is a two-round form of voting where the top two candidates from the first round go on to the final round, and it is the winner of the final ‘run off’ round who wins the election. But in our system, instead of having to hold a second ‘run off’ election a month later, we collect everyone’s preferences and do the ‘run off’ part in the same count to determine the winner more quickly.

By numbering your preferences you are basically saying “If my number 1 candidate doesn’t win, I want my vote to go to my number 2. If 1 and 2 are unsuccessful, I want my vote to go to number 3.” And so on, for however many candidates there are on the ballot paper.

And that’s exactly how it gets counted on election night. The votes get put into stacks for each candidate. The candidate with the fewest votes is excluded. As each candidate is knocked out, each vote from their stack is redirected towards whomever that voter numbered next in their sequence. The votes are tallied again, the one with the lowest number of votes is excluded again, and their votes redistributed.

This process continues until there is a winner. So at the end of the count, there are only two candidates left in the count for the House of Representatives – and this is what you’ll see in the ‘two party preferred’ count on the television.

The Senate elects a number of people, so at the end of their count, there are all the winners plus the first runner up left in the count, with all other candidates excluded. This is explained a bit more below.

Preferences for the House of Representatives

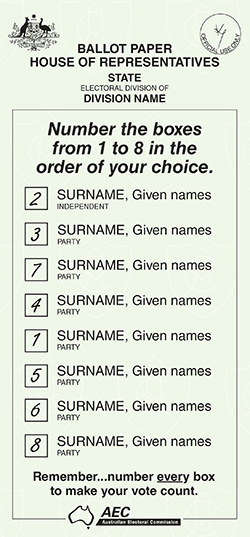

For the upcoming federal election, on the green House of Representatives ballot paper you need to number every box, in sequence – not having a number repeated anywhere on the ballot paper.

So if there are 8 candidates on the ballot paper, like in the picture, you number all 8 boxes, using all the numbers from 1 through to 8 – 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8.

You number the candidate you want to vote for 1, the candidate you like second best 2, and so on. The last number should be against the candidate you really don’t want to win. The only candidate your vote will not go to is the one that you put last.

You can practice voting for the House of Representatives here https://www.aec.gov.au/Voting/How_to_vote/practice/practice-house-of-reps.htm

Importantly, your vote is not worth less as it goes through the preferences, it’s worth one vote regardless of which candidate got your vote in the end. And only you decide who gets your vote.

Preferences for the Senate

Preferences for the Senate are a bit different. You vote the same way – you number the boxes in order. But you can either vote for party groups above the line, or individual candidates below the line. You cannot vote both above and below the line – pick one and stick to it.

You do not have to number every box on the Senate ballot paper.

- If you vote for party groups above the line, you must number a minimum of 6 boxes in sequence

- If you vote for individual candidates below the line, you must number a minimum of 12 boxes in sequence

You can vote for more than the minimum if you wish, up to numbering every candidate.

If you vote above the line, the force and effect is that you voted for every candidate below the line in the order in which they appear. So all the candidates under your number 1 first in order, then all the candidates under your number 2 in order, and so on.

If you vote below the line, then your vote will count only for those candidates whom you put a number against.

The preferences again are counted by the order you indicated. As each candidate or group is knocked out, your vote goes to the next vote in sequence.

If your candidate is elected, your preferences after that will still flow on, but at a reduced rate – so less than a whole vote. This is because it is not possible to determine which votes actually elected the candidate and which votes are surplus, all the elected candidate’s ballot papers are transferred at a reduced rate.

Note: The Australian Senate elections are one of the most complex in the world and there are only a handful of people that really understand it completely. The important part to understand is that you decide where your votes go. If you don’t number a candidate below the line, or their party square above the line, your vote will not count for them.

Why there’s so much confusion about preferences and ‘party preferences’

Once upon a time, the Senate system allowed you to vote for just one party group above the line. The party – not the voter – would then decide where the preferences for that vote would go to.

Parties would do these very complicated deals to swap votes, and then lodge a preference flow with the electoral commission.

This system – and any control parties had over preferences – ended in 2016.

In 2016 the Senate voting system was changed to remove the use of group voting tickets; and to require voters to allocate six or more preferences above the line or twelve or more below the line on the ballot paper.

However, because most people in Australia don’t pay much attention to elections, there is still a widespread belief that parties control preferences. They do not.

What about the How to Vote cards?

How to vote cards are quite an unusual and very Australian thing. Largely a quirk of the fact that we have a very complicated voting system and compulsory voting – which means a large number of people turning up to vote without any clue what to do or who to vote for – the ‘How to Vote’ information proved a very influential marketing device.

But it is just that – a marketing flyer or brochure. So now when people talk about ‘preference deals’ all they are talking about is parties and candidates agreeing to promote each other in their marketing. It has no effect on how your vote is counted.

How to Vote cards are so woven into the culture of Australian elections now that people think they have some official purpose. They do not. It’s just a form of advertising.

If you find it helpful, then by all means take one, but you do not have to follow a ‘How to Vote’ card to vote correctly and have your vote counted.

You do not have to take a ‘How to Vote’ flyer as you enter the polling booth at all.

If a candidate’s ‘How to Vote’ material has only a 1 on it next to where their name appears on the ballot paper, and doesn’t number other boxes, you do still need to number all the boxes.

Important things to remember:

- Only you decide where your vote goes and who gets your preferences.

- Parties have had no control over preferences in federal elections for a decade.

- How to vote cards are marketing brochures only, and you do not need to follow them.

We’ll do a more specific ‘how to vote’ explainer using the actual ballot papers once the candidates are finalised.

Follow all the New England Times coverage of the federal election here or have your say on Engage

See more about the race in New England here

See more about the race in Parkes here