One of the most common refrains you’ll hear anytime commentators are talking about the New England electorate is that it’s a ‘very safe National seat’. But is it?

What is a ‘safe seat’?

The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) classifies electorates as safe, fairly safe or marginal. In a safe seat, the winning party receives more than 60 per cent of the vote; it would require a very large swing – change in votes – for the incumbent candidate to lose this seat at the next federal election. ‘Fairly safe’ is any seat where the winning party receives between 56 and 60% of the vote, and any seat where the winning party gets below 56% of the two party preferred (2PP) vote is categorised as marginal.

To complicate matters, the categorisations the AEC uses may not be the same as particular pollsters or journalists. Antony Green, the ABC’s highly respect election analyst (who has announced this will be his last election) sets the maximum possible swing in his calculator at 10%, and classifies any seat with more than a 10% margin as ‘very safe’.

But the general principal is the same: a marginal seat is one that could very easily change hands, where as a safe seat would be harder.

The reasoning behind this is anchored in years of watching elections and analysing voting statistics – Australian elections are usually very stable, and very tightly contested, with the national 2PP usually within 2% of a dead heat. To get a swing in a particular seat outside of the trend – that is more than 5% – is pretty hard to do and usually requires something spectacular.

Why is New England considered a safe seat?

Quite simply because of the voting results of the last election, there are no other factors that come into the assessment.

Barnaby Joyce (NAT) defeated Laura Hughes (ALP) with a two party preferred vote of 66.43 to 33.57. That’s a margin of 16.4% (the percentage above 50%), which is a safe seat in AEC categorisations, and a very safe seat in Antony Green’s.

There has been a redistribution for this election adding the balance of Gwydir Shire and all of Muswellbrook Shire to the electorate, which alters the nominal margin of the seat. In the simplest terms possible, you add up the results of booths that were in Parkes or Hunter in the last election but will be in New England for the next one, combine them with the actual New England results, and recalculate the 2PP.

Again deferring to the master, Antony Green has calculated the post redistribution margin of New England to 15.2% – or 1.2% of the vote shift in Labor’s favour. The seat is, however, still categorised as very safe. You can read more about his processes and thinking on this here.

Has it always been a ‘safe seat’?

No.

New England has been held by Country or National Party MPs for most of its history since it was established in 1901. But the borders of what are the New England electorate have changed over time, as they are at this election, and it has, at times, been a marginal seat. Additionally, preferential voting was introduced in 1918, but it wasn’t until the 1940s that this notion of two party preferred figures started being reported in election results, and it took until the 1980’s and the work of Malcolm Mackerras to import the ‘pendulum’ method of predicting elections before discussions of 2PP and swing started to dominate election analysis.

So, let’s start from the 1980s and have a look. Note this table is using two candidate preferred margin, not two party preferred – this is nerdy stuff, but as New England is rarely a Coalition v Labor contest, the best way to assess it is on a two candidate preferred basis and just looking at the swing for or against the Nationals.

New England Electorate margins 1980-2022

| Election | Winner | Party | 2CP Margin | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | Ian Sinclair | National | 6.5 | Safe |

| 1983 | Ian Sinclair | National | 5.4 | Marginal |

| 1984 | Ian Sinclair | National | 4.6 | Marginal |

| 1987 | Ian Sinclair | National | 8.4 | Safe |

| 1990 | Ian Sinclair | National | 6.3 | Safe |

| 1993 | Ian Sinclair | National | 10.2 | Very safe |

| 1996 | Ian Sinclair | National | 19.18 | Very safe |

| 1998 | Stuart St Clair | National | 12.93 | Very safe |

| 2001 | Tony Windsor | Independent | 13.85 | Very safe |

| 2004 | Tony Windsor | Independent | 21.0 | Very safe |

| 2007 | Tony Windsor | Independent | 24.33 | Very safe |

| 2010 | Tony Windsor | Independent | 21.52 | Very safe |

| 2013 | Barnaby Joyce | National | 14.46 | Very safe |

| 2016 | Barnaby Joyce | National | 8.52 | Safe |

| 2017 By-election | Barnaby Joyce | National | 23.63 | Very safe |

| 2022 | Barnaby Joyce | National | 16.43 | Very safe |

Ian Sinclair was first elected in 1963 and held the seat for a very long time, most of that winning solidly on primaries (that is, on first preference votes, not requiring other votes to get him above 50%). But for two elections – the Double Dissolution election in 1983, and the 1984 election Bob Hawke called 18 months early to realign the Senate and House electoral cycles, the seat was marginal. There are some other earlier results that are marginal too, but the differences get bigger the further back you go.

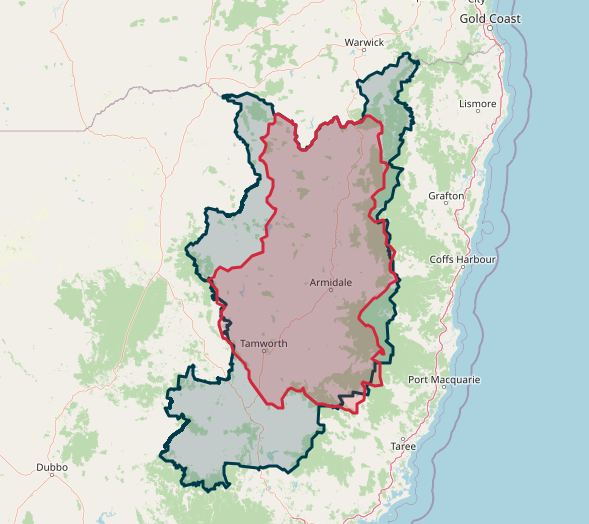

If you’re wondering how different the electorate was for each of these elections, the Parliamentary Library has this great little tool where you can just click on the different periods to see an overlay of the maps. This shows the map as it was in 1983, when the seat was marginal, in red, and the seat at the last election in dark green.

Is a ‘safe seat’ actually safe?

No.

The classifications of ‘safe seat’ do not take into account the personalities and credentials of candidates, voter psychology, significant social events, policy issues, or anything like that which might actually affect voter behaviour – it’s a simple categorisation based on the result at the last election.

One of the things you’ll notice in the table above is that the seat was believed to be ‘very safe’ each time it changed hands from National to Independent and back again. The occasions it was marginal it did not change hands.

New England, like most regional seats, is historically stable, with the shift in voting results each election in the normal range of around 3%.

When there’s a swing on, the New England swings hard, often into double digits. For example, when Tony Windsor beat Stuart St Clair, there was a 21.23% swing against the National Party. The following election there was another double digit swing of 12.7% against the National Party. When Barnaby Joyce won in 2013 it was with a 35.98% swing back to the Nats.

A lot of that has to do with the culture of New England. We are a very interconnected and classically conservative community (that is, resistant to change unless its necessary, not ideologically conservative). So we tend to stick with what we’ve got until we don’t, and when we do have a change of mind – on anything – we tend to move quickly and together.

In Barnaby’s tenure New England has been a lot more volatile, with swings above 5% in every election he has faced except for 2022 – which kinda doesn’t count because it was COVID-19 affected. There is a significant chunk of the current electorate that will vote for a decent independent if there is one on the ballot, but will return to the National Party if there isn’t, which is pretty easy to see in the swing patterns.

The other factor to consider is that the New England is one of the most politically engaged electorates in the country, with one of the highest levels of awareness who our federal member is, and political discussion among friends and family common. That means we are more interested and informed voters than a ‘typical’ seat, and as a result of that, more likely to shift our vote when presented with a better option. The hardest part of election campaigning is getting people to listen in the first place, and a lot of us are already listening – which makes campaigning in New England much easier than say inner Sydney.

So, while a 15%+ swing seems like a massive obstacle to overcome, New England is actually easier to win than a typical marginal city seat. You just need the right (independent) candidate and a decent campaign.

Is the New England likely to change hands this election?

No.

Since 2022, we’ve also have a very dramatic shift in our population profile thanks to both COVID-19 refugees fleeing the city, and a significant number of Lismore residents who decamped to higher ground after their series of devastating floods. We don’t know yet what that will do to the vote this election, but the combination of those two influxes from largely left-leaning areas, added to the addition of Muswellbrook, is a lot of new voters who have no existing loyalty to Barnaby Joyce or the National Party.

But, in order for them, and the substantial block of New Englanders who will vote for a decent independent if there is one, to vote for an alternative, there has to be a credible alternative on the ballot.

(This, by the way, is the fundamental problem with most analysis of New England elections and voters – they all assume there was a credible alternative to vote for.)

At this stage, there is only Labor’s Laura Hughes, who ran in the last election, and One Nation’s Brent Larkham are declared candidates (that we are aware of). Natasha Ledger said in an interview with another outlet she would be running again, but as yet hasn’t updated her website from the Northern Tablelands election last year.

While Hughes is a competent person and has a lot of things in her favour this election, the plain reality is that without a strong independent in the field to pull away that 10% of the vote, the seat will stay with the Nationals. Even if Barnaby was to announce tomorrow he wasn’t running, that chunk of would-be independents will stay National unless given a credible independent alternative.

For a decent independent to contest the seat properly, get to all the communities and generate the necessary name recognition and momentum, they needed to start campaigning about… 8 months ago. New Englanders are resistant to change and slow to trust, so at this point the only viable independent candidate who might give Barnaby a run for his money would have to be someone who already has a very high name recognition and support across the electorate.

What about Parkes?

Parkes is a difficult seat to campaign in. Unlike New England, it doesn’t have a common identity or community, even the most active campaigner can’t reach every small village and town, and the vote is much more party based as a result.

Historically, the seat is safe National. And it’s likely to stay that way, unless someone with a massively high profile, a lot of money, and ideally a plane, wants to contest the seat.

There was one absolute squeaker in 1993, when Dubbo author Barry Brebner nearly won the seat for Labor, and left the seat one of the most marginal at 0.53% margin, but it is a fun historical aberration.

Follow all the New England Times coverage of the federal election here or have your say on Engage

See more about the race in New England here

See more about the race in Parkes here