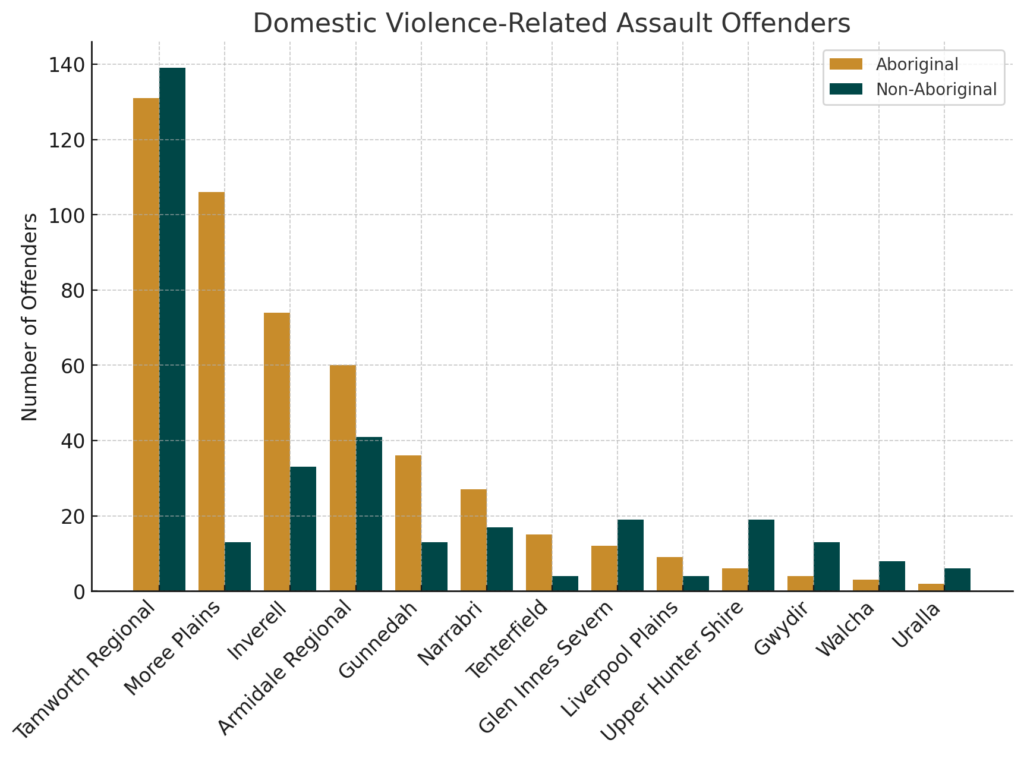

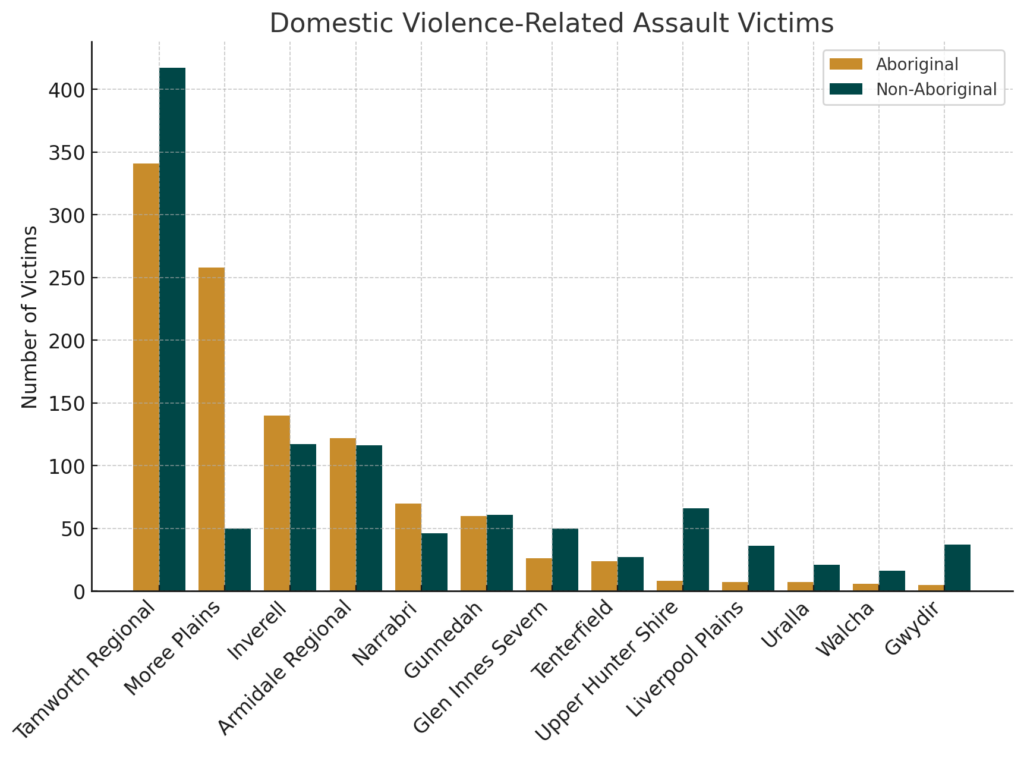

Twelve per cent of New Englanders identify as Indigenous. But they make up 46 per cent of known local DV victims.

An Indigenous men’s behaviour change program in the New England region could be the missing piece of the puzzle to put the brakes on domestic violence locally.

In part two of our New England Times investigation by Lisa Martin, we learn that a funding shortfall is robbing families the chance to heal and reunite.

From sleeping in a park with a shopping trolley to managing a retail store.

That was the journey of an Aboriginal man who underwent an Indigenous men’s behaviour change program aimed at domestic violence perpetrators in Victoria.

Spending time with other Indigenous men “on country”, healing years of suppressed trauma and taking responsibility for his violent behaviour saw the man, eventually gain his family’s forgiveness, move home and have his kids returned from child protection.

But in the New England, Indigenous men are being denied the chance to break their cycle of violence because no equivalent specialised culturally appropriate program exists.

The only NSW-registered domestic violence Indigenous men’s behaviour change program is Gawura, which operates on the NSW south coast. Waminda, an Aboriginal community-controlled organisation in Nowra has successfully obtained a state government grant to set up an Indigenous men’s behaviour change program and is in the process of registration.

(Brothers in the Dale, a community corrections program curbing reoffending in Armidale – is only open to Indigenous men already in the justice system.)

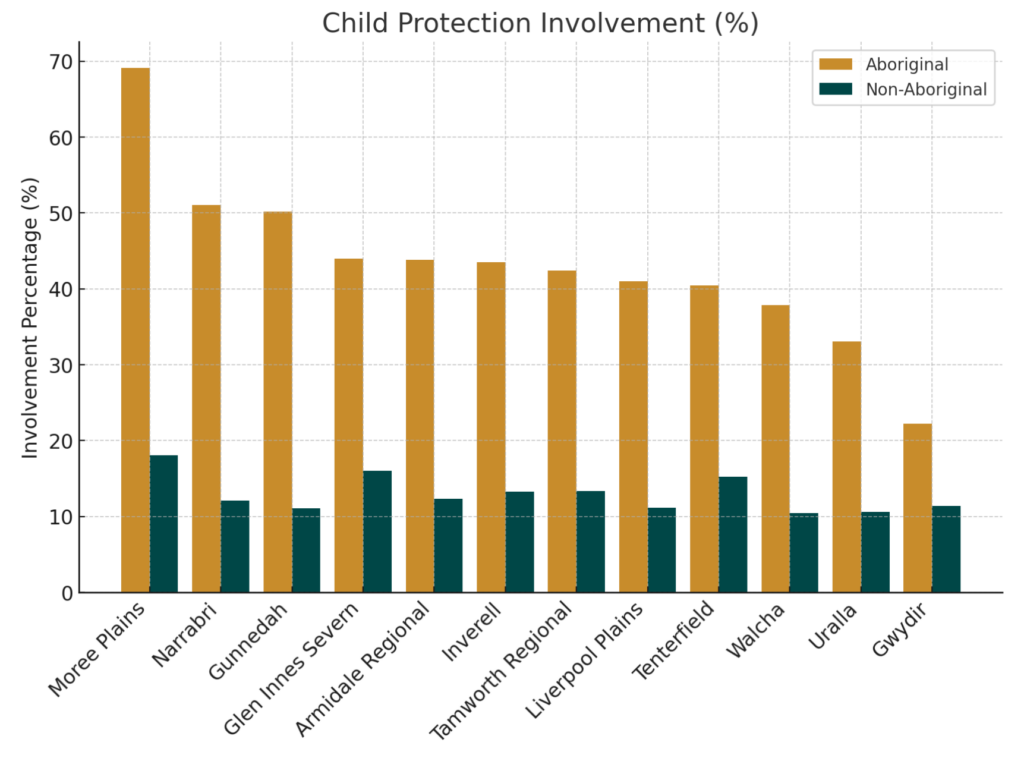

First Nations people make up more than 11.9 per cent of the New England population, according to census data, but are significantly overrepresented in domestic violence statistics, with 46.3 per cent of victims identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander.

NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research – local government area data July 2023- June 2024 on the Aboriginality of alleged offenders and victims in domestic violence-related assaults.

Lack of funding, not lack of demand or desire

In 2021, Armidale was pushing to set up a registered domestic violence indigenous men’s behaviour change program. An Alice Springs expert visited to provide insights, and a task force undertook community consultations and preparation work.

Women’s Shelter Armidale – which has a client base of two-thirds Indigenous families – was set to team up with Armajun Aboriginal Health Service on a pilot.

However, the project never moved into operation mode because of a lack of money.

“Without a men’s behaviour change program, our men go to jail,” Armajun Aboriginal Health Service family healing case worker Jusinta Collins told the New England Times.

It costs taxpayers $120,000 per prisoner to jail someone for a year, according to the Productivity Commission.

An Indigenous men’s behaviour change program could be a bargain – $600,000 a year to operate on a skeleton staff, says Women’s Shelter Armidale chief executive Penny Lamaro, adding that no funding is available.

“I would say it’s one of the missing pieces (of the puzzle),” Ms Lamaro said.

Demand for such a program would be strong Ms Collins noted, saying her caseload across Armidale and Walcha was double the 10 she is supposed to have at any one time.

Male perpetrators that she encounters are desperate to engage and be better dads, Ms Collins said.

Many saw domestic abuse first-hand as children and had multiple out-of-home-care placements with white families which disconnected them from their culture, she said.

Family violence was never a part of traditional Indigenous culture, according to a 2021 report by Our Watch, an independent organisation campaigning against domestic violence. Multiple studies have found violence in Indigenous peoples is shaped by the historical context of colonialism, forced removal of children, systemic disadvantage and intergenerational trauma.

Centacare Tamworth runs a men’s behaviour change program called Disrupting Family Violence, but Ms Collins said none of her Indigenous clients have gotten into that program.

Ms Lamaro noted the Tamworth program was “over-subscribed”.

“It can take as long as 12 months to get an invitation to participate,” she said.

Centrecare NENW confirmed to New England Times that there is a waiting list for that program, but a Department of Communities and Justice spokeswoman denied that the Centacare program had a waiting list and said it was “inclusive to all men” and that “Aboriginal men regularly” participated. She said Centacare collaborated with local Indigenous organisations in the region.

Children pay the highest price

In NSW, health workers, social workers, teachers and police are legally required to make mandatory reports to authorities if they encounter a child exposed to domestic violence. In New England, like in other parts of Australia, Indigenous children are removed from violent households at a greater rate than non-indigenous youngsters.

Children and youth in out-of-home care in the New England region 2019-2024, by Aboriginality. Source: NSW Department of Communities and Justice.

When the NSW Department of Communities and Justice places children into out-of-home care, a caseworker draws up a “family action plan” with parents that addresses safety concerns and goals.

Ms Collins said the plans she sees often have something to do with men’s behaviour change.

“You’re basically setting the family up for failure… If you don’t achieve the action on the family action plan your child doesn’t come back home. Your child goes into the system (parental responsibility) to the Minister until they are 18,” Ms Collins said.

Once they are in the system it is near impossible to get them out.

During her 30-year career, Ms Collins has only seen one family do it.

The NSW Department of Communities and Justice said it was unaware of “any concerns from providers in the New England district about the family action plans being unachievable”.

“Taking part in a men’s behaviour change program is not a mandatory requirement to get children back from out-of-home care,” the spokeswoman said.

She said Men’s Line (counselling hotline) may also be consulted for other options if timely access to men’s behaviour change programs is unavailable.

Hope in examples elsewhere

Elsewhere in Australia, Indigenous men’s behaviour change programs are transforming lives.

Victorian-based Aboriginal organisation Dardi Munwurro established what is believed to be the world’s first residential family violence Indigenous men’s behaviour change program.

“We had a man, who was pushing a trolley around, sleeping in a park,” Dardi Munwurro director Alan Thorpe said.

“When he came into the men’s group, his kids were in child protection, he had family violence and was in the system. He did a lot of work and healing. He gets his kids back. He now lives with his family and kids in a house and works as a manager in a large retail store.”

On average 250-300 Indigenous men undertake Dardi Munwurro programs each year. Fifty are on a waiting list for the 16-week, 12-bed residential program.

The organisation established in 2000, works with adult perpetrators on healing and also carries out violence prevention work with indigenous youth from ages 10-18.

“The only ones who can fix it is us,” Mr Thorpe said.

“I always say if we are the oldest living culture in the world, we know some things.”

A Deloitte 2021 cost-benefit analysis said the biggest advantage of Dardi Munwurro programs was reduced incarceration rates – from 13 per cent pre-program to four per cent post-program.

Every avoided case of incarceration saved taxpayers more than $90,000 per annum, the report said.

“As long as they are committed to their healing, we walk side by side with them on that journey until they feel they don’t need us anymore,” Mr Thorpe said.

This is part of an investigative series about domestic violence in the New England. Join us tomorrow for part three as we look at what happens to victims when there are no police to turn to.

WHERE TO ACCESS SAFETY AND SUPPORT FOR FAMILY VIOLENCE

- Police – 000

- Empower You – NSW Police app for documenting abuse and accessing support

- Women’s Shelter Armidale – 1800 005 352

- Sora (Formerly Tamworth Family Support Services) – 1800 073 388

- Centacare New England – 1800 372 826

- Anglicare – 02 6701 8200

- Gunnedah Family Support – 02 6742 1515

- Allawah Cottage Gunnedah emergency accommodation – 02 6742 4193

- Armajun Aboriginal Health Service – 1800 276 258

- Aboriginal Legal Service NSW – Tamworth, Moree, Armidale 1800 765 767

- Women’s Domestic Violence Court Advocacy Service – 1800 938 227

- NSW Domestic Violence Legal Advice Line – 1800 810 784

- Domestic Violence Line NSW 24/7 statewide crisis counselling and referral service – 1800 65 64 63

- NSW Victim Services counselling and financial support for victims of crime

- 1800RESPECT 24/7 national domestic, family and sexual violence counselling service

- Mensline 24/7 phone and online counselling for men – 1300 78 99 78

- eSafety Commissioner – online safety checklist if you’re experiencing tech-based domestic, family and sexual violence

- Kids Helpline 24/7 phone counselling with young people aged 5-25 – 1800 55 1800